Martin Parr. Short and Sweet

MUDEC, Milan

From February 10th, 2024 until June 30th, 2024

At the age of twenty-three, Martin Parr, alongside Susie Mitchell, swiftly navigates through the suburbs of the London metropolis towards the outskirts of Yorkshire. For five years, the couple diligently documents the daily events they encounter, particularly those involving the Non-Conformists, a name inspired by the Methodist and Baptist chapels that were becoming numerous in the area. Influenced by the American color photography of William Eggleston and Garry Winogrand, Martin Parr captures both the surrounding environment and the lives of the so-called blue-collar workers: laborers, miners, farmers, gamekeepers, and pigeon fanciers, thus creating a historical and poignant documentary portrait capable of defining the fiercely independent character of a Northern England seeking to separate itself from the Anglicism of the State. Through a photographic chronicle devoid of filters and anti-rhetoric, the exhibition dedicated to Martin Parr at the MUDEC in Milan appropriately commences with The Non-Conformists, a series of images taken from 1975 to 1980 by a young and unpublished photographer destined to soon earn recognition from the global audience.

“Normally, you’re told to photograph only when the light is good and the sun is shining, but I liked the idea of taking photos only in bad weather, as a way to subvert the traditional rules”.

Parr’s first bold, energetic, and saturated color project is The Last Resort, a bitterly ironic reportage conducted on the beaches of Brighton, a seaside suburb of Liverpool, in the early 1980s, a period of deep economic decline in the northwest of England. Between satire and subtle cruelty, Parr portrays low-income families on vacation in New Brighton: through Parr’s lens, what should have appeared as a summer resort looks gray and chaotic, resembling an industrial area. Parr evokes nostalgia for the 1960s, creating the first example of ruthless and clear-eyed reportage on the demise of a world—the working class—and its values and non-values, as well as the unstoppable rise of a new consumeristic conception of life. On the same wavelength is Common Sense: over 200 A3-sized photographs offering a close study of mass consumption and the waste culture, particularly in the Western and European context. Combining all the elements that had characterized Parr’s photography in the 1970s and 1980s, the series follows the artist’s obsessive visual exploration of everything discordant, vulgar, and absurd. When presented to the public, Common Sense appears as a broad and cohesive series of brightly colored images printed inexpensively, thanks to a color Xerox machine. Parr excels here in depicting subjects often associated with bad taste and contemporary vulgarity, which he captures with underlying cynicism and unprecedented sarcasm.

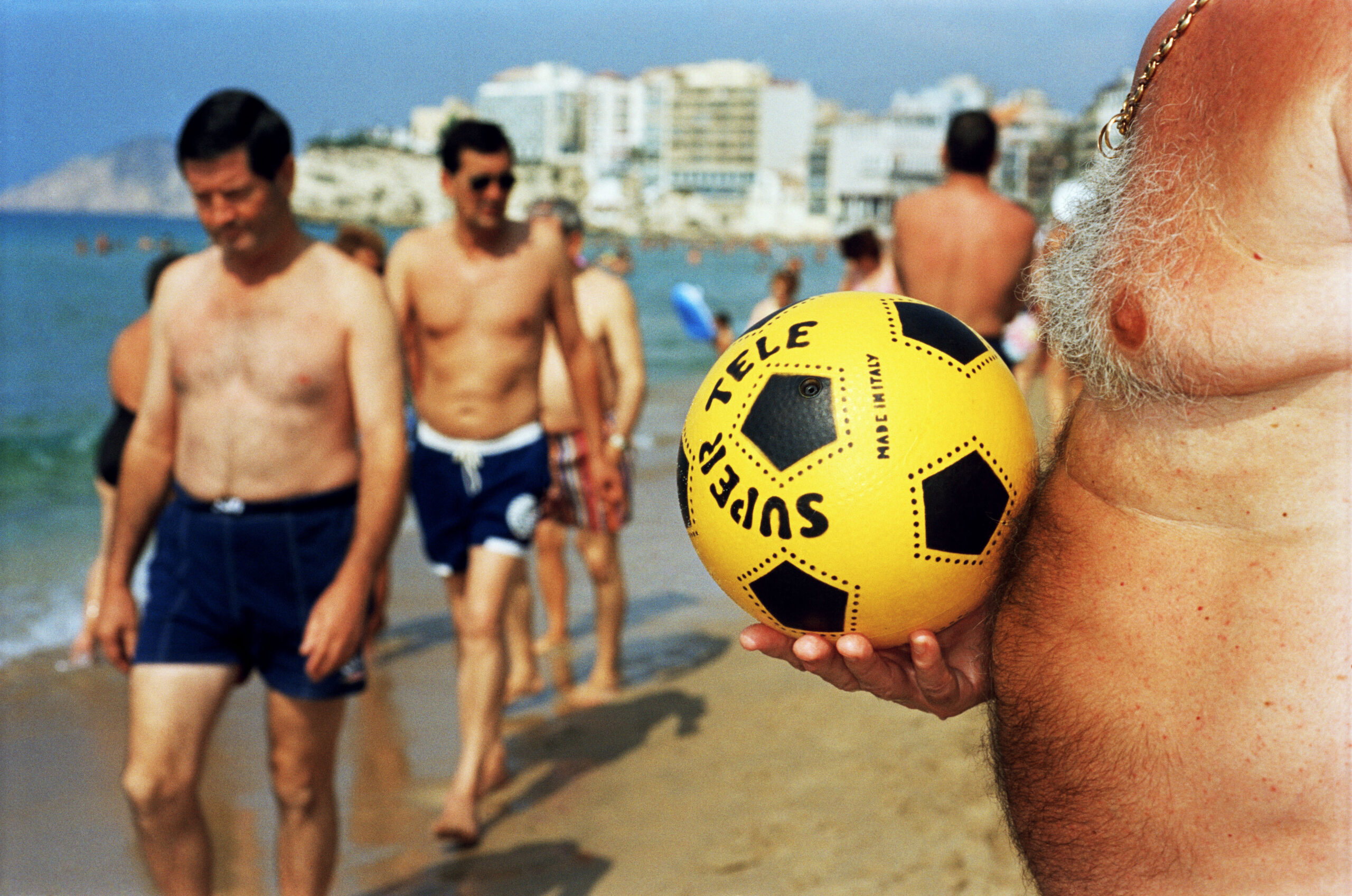

The shots and dynamic compositions, made of bold juxtapositions, kitschy objects, and heavy faces, are captured from unusual angles and close-up frames to seize the attention and interest of the observers. Paying attention to detail becomes fundamental, through which Parr manages to capture the distinctive elements of a place or situation, along with a careful analysis of the culture and society he is describing. In the nineties, Martin Parr’s gaze broadens and turns to the rest of the world; in Small World, he explores the realm of mass tourism on a global scale, highlighting an increasingly homogeneous perspective of travel where, in the pursuit of different cultures, those very cultures are destroyed. The issues raised by Parr a decade ago are even more relevant today: while lively groups of tourists appear as enthusiastic participants in a ubiquitous consumer culture, they are also perplexed victims at the mercy of larger social forces and trapped in the desire for spectacle. The photographer Parr follows in the footsteps of the average tourist and attempts to reveal the great farce of travel, which for most people is actually a leisure activity made possible only recently, following the development of low-cost airlines. A particularly cruel, standardized mirror to the point of absurdity, of the tourism world that increasingly resembles a diluted and homogeneous dream.

Alongside tourism, there is also the theme of dance: Everybody Dance Now. According to Martin Parr, apart from photography, dance is probably the most democratic form of expression. He combines the two arts in this exploration, starting from São Paulo in Brazil and extending to the Scottish islands, photographing various types of dancing for over thirty years: street dancers, aerobics classes, parties from around the world, tea dances. Parr’s work is always a precise study of bodies, their proportions, and their skin, their movements, different clothing, footwear, makeup, and facial expressions in that particular activity of leisure time, which is natural yet deeply cultural: dance. His shots reveal a wild energy, where the collective body manifests itself without reservations or inhibitions. But in the end, England remains Parr’s favorite subject matter: most of his photographic series, whether comical, dogmatic, affectionately satirical, or colorful, are dedicated to documenting what it means to be british today. With Establishment, the photographer continues by capturing the elites who govern the country and their rituals, making the obvious surprising, reinventing clichés, and transforming them into provocative revelations. Here are the places and prominent figures of british politics, centers of power, and the most famous universities. The social conventions that repeat over time, behaviors analyzed down to the smallest gestures, clothing, expressions, looks, small obsessions, and traditions expressed in furnishings and objects.

In America you have the street, in England we have the beach.

Life’s a Beach showcases shots from beaches around the world, in a kaleidoscope of images of clothed and unclothed bodies, and their display in public. In the United Kingdom, it’s impossible to be more than 75 miles from the coast, and with so much sea, it’s no surprise that there’s a strong tradition in Britain of taking photos on the beach; for Parr, it’s where people can relax, be themselves, and display all the little quirks of behavior that are typical of the British. The result is a systematic and non-judgmental analysis of our everyday pleasures, in which we are all equal when our feet sink into the sand, when we wait for the moment we can immerse ourselves in the water and find pleasure in those universal and ritualistic gestures common to any class and social background. Through his projects, the documentary style that has characterized Parr’s language for over fifty years becomes a litmus test for observing contemporary society and its most contradictory facets, those belonging to the Western world, particularly Europe, rendered through unfiltered and non-rhetorical photographic chronicles, sometimes told with sharp sarcasm; more often presented with cutting humanity.