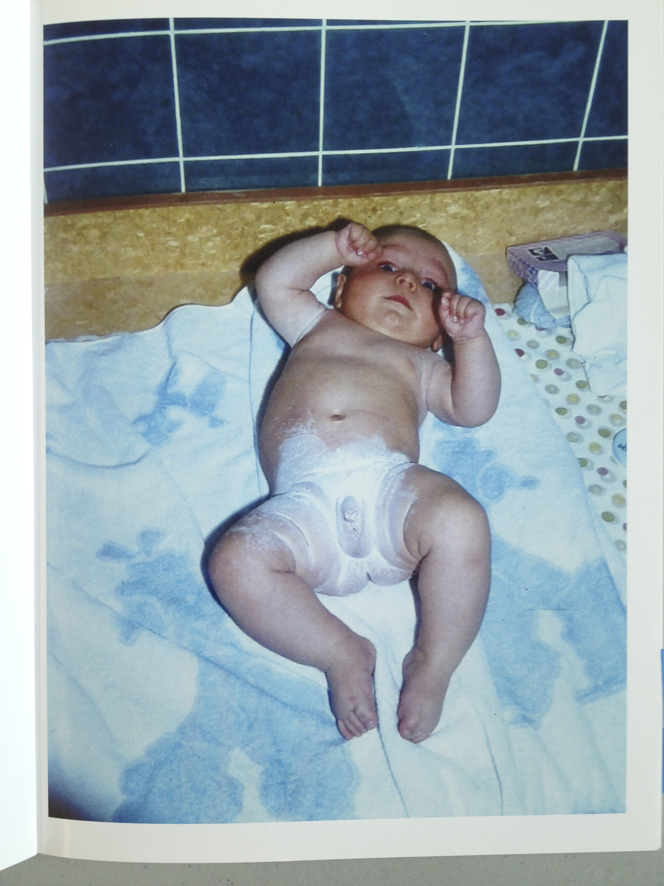

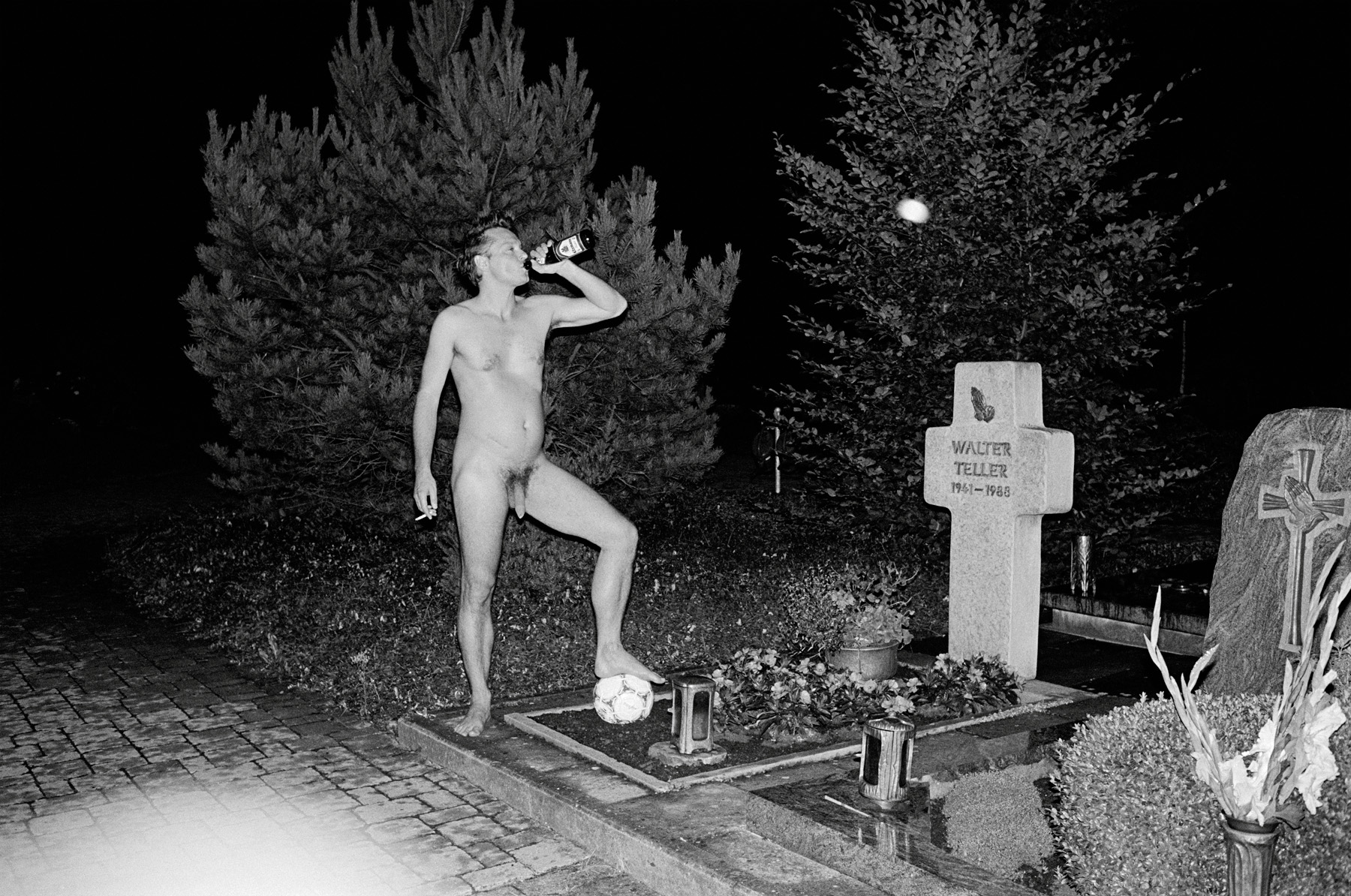

The journey of i need to live is a syncretic excursion combining two opposing temporalities and two antipodal life postures experienced by artist Juergen Teller. The photographer decides to start precisely with a photograph of himself, still a very young child, taken by his father, and then crosses decades of personal and professional work, culminating, cyclically, with photographs of his newborn daughter. Thus, from the earliest works one can read two opposing drives destined to explode with a strong visual impact in form and ironic in meaning. On the one hand, the will and desire to live, to believe in the future and in the infinite potential reflected in a child and in one’s own family; on the other hand, the artist’s biographical past, which recalls her father’s heartbreak, depression and untimely death. Two opposing postures towards life, of which the photographer mocks, as in the quasi-self-portrait Father and Son (2003), where he self-portrays himself naked on his father’s grave while drinking a beer and smoking a cigarette. It is as if for Teller the camera acts as a liberating medium, a tool that syncretically combines two opposing attitudes, death and the will to live, self-sabotage and curiosity about life. On display are instantly recognizable images-such as the portrait of Björk and her son, taken in Iceland’s Blue Lagoon in 1993-and others never before exhibited; all displayed in a space all displayed in a space designed by 6a architects, which imagined the photographer’s concrete-clad studio in West London.

“The title of the exhibition i need to live is meant to express a positive message and a strong statement, namely that I am still super curious about life.”

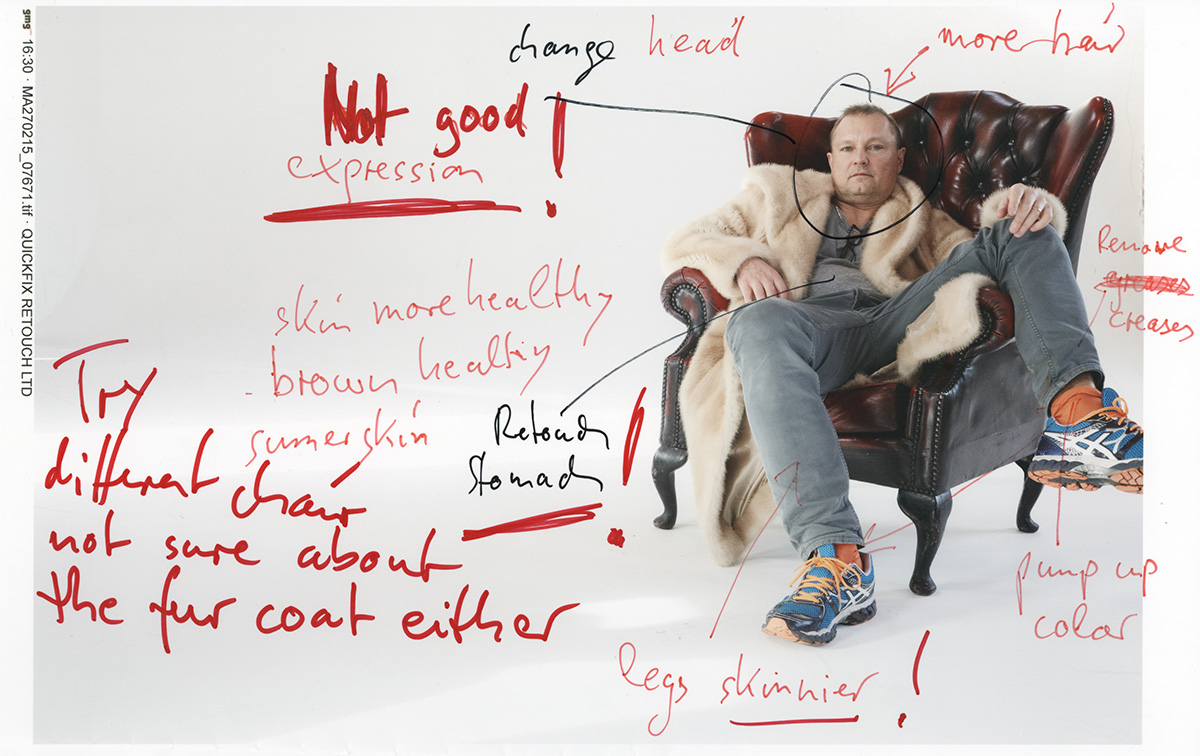

Emerging in the late 1980s, Teller has always rejected in his work the references for which that decade was known-money, excess-in favor of a freer vision of reality. In the intervening years, he has made a reputation for his no-frills work that favors grit over glitz, grunge over glamour; his photographs often appear unposed and unstaged, everything in his images is in favor of inspiration in spite of a fake, schematic construction. Teller is now known for his irreverent images and the influence of his work in fashion photography and the visual arts, which has become one of the greatest in an all-encompassing and all-embracing way that it is difficult to detach him from contemporary fashion photography. Creative director Anthony Vaccarello describes him as “an extraordinary photographer whose intelligence, humor and respect make his work a real introspective game, where flashbacks are both tributes and allusions to the founding myths of the Maison Yves Saint Laurent.” And it is true that the genius of the German artist’s photographs lies in the fact that it seems that anyone can produce them, but no one else can. As one traverses the exhibition, toward the end, the sense of the early works that looked back to the past is reversed, as one finds oneself building for the future: photographs of the artist’s wedding in 2021, a series on the conception of her first child, and other works after her birth, conclude, as if to suggest a sense of optimism and vitality, the exhibition. “It’s about being positive,” the artist declared at the opening of I need to live.

The reversal of meaning, something that changes the point of view and makes everything less obvious, is the focus of the exhibition and the common thread throughout Teller’s body of art, especially in his works of advertising, in editorials and in his more personal and intimate works. His way of being present is never overly exaggerated toward a situation and its outcome, as if Teller is particularly keen to maintain a kind of freedom and openness toward what is going on between him, his subjects, and his collaborators. With clients like Marc Jacobs or Helmut Lang, the strong relationship of mutual trust allowed him to dig deep and create the best possible work, in his own way. So whether working with a fashion designer, stylist, curator, or artist, or with Cindy Sherman or Nobuyoshi Araki, creative fellowship remains the most important creative element.

For further information grandpalais.fr