Pino Pascali

March 28th – September 23rd, 2024

Fondazione Prada, Milan

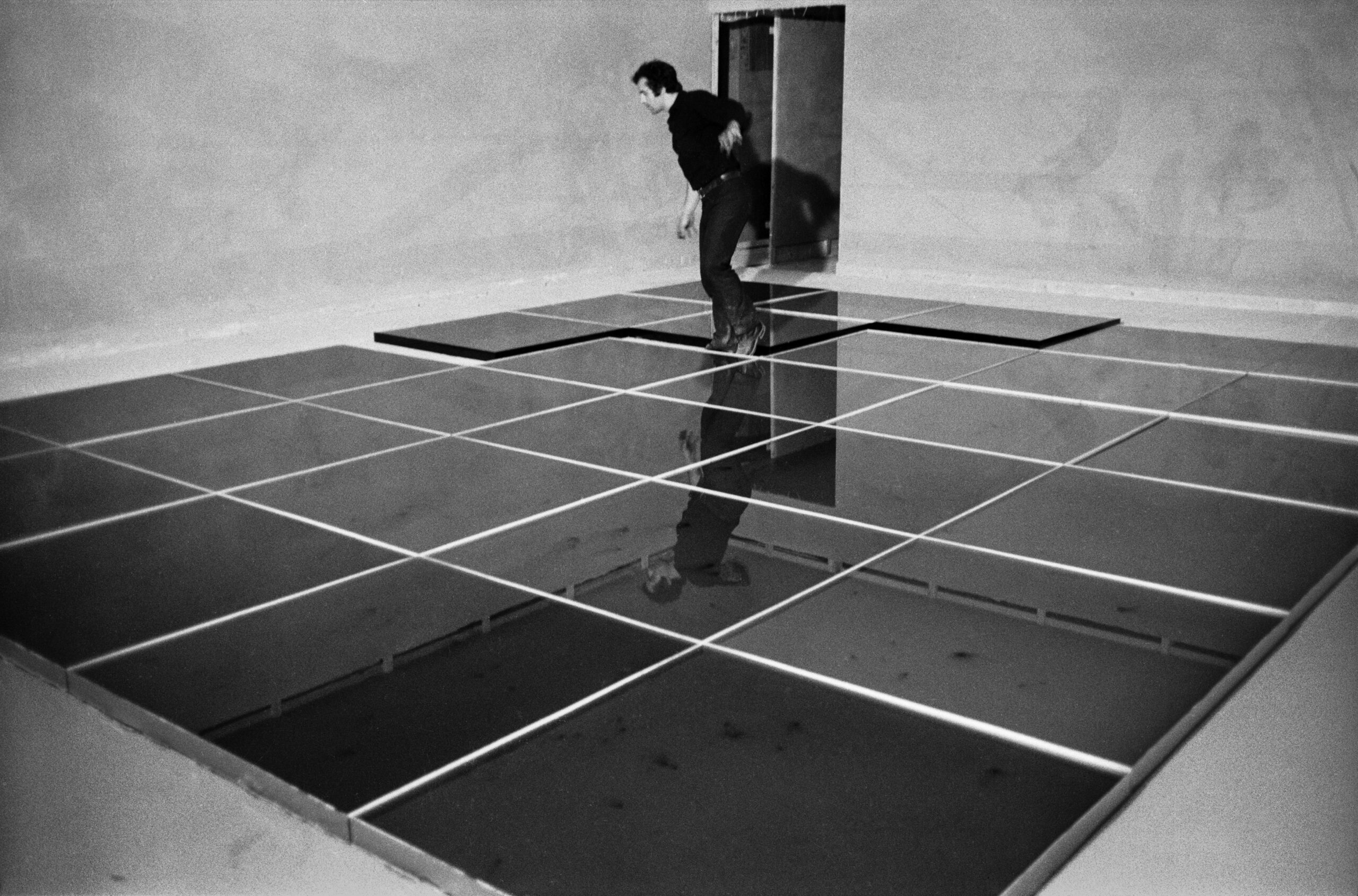

Born in Bari in 1935, Pino Pascali moved to Rome in 1955 to study set design at the Academy of Fine Arts. Since his Academy years, under the guidance of Toti Scialoya, Pascali studied Pollock, Gorky, and De Kooning, fathers of American abstract expressionism. The vital energy, the chaotic rhythm, and lack of reasoned form attracted the young student, especially Pollock’s dripping, which marked a clear boundary with figuration – a boundary Pascali would never abandon. Fascinated by the use of unusual materials such as bitumen, milk, leather, and metal, he experimented with mixtures of petroleum and various powders, painting on zinc and wooden sheets. Pascali loved paradox, nonconformity, the gesture that would provoke astonishment; he drove around Rome in an old car, always dressed in black, volcanic and intolerant of rules; he was enchanted by zoo cages and toy shop windows. In 1968, he tragically died in a motorcycle accident at the age of thirty-two, the same year as his solo presentation at the Venice Art Biennale. This year, Fondazione Prada presents an extensive retrospective dedicated to Pino Pascali, which unfolds across three buildings of its Milan headquarters: the Podium, the North Gallery, and the South Gallery.

As Mark Godfrey writes, Pascali explored the relationship between sculpture and stage elements and juxtaposed sculpture and everyday objects. He created works that from afar seemed like ready-mades, but upon closer inspection revealed themselves to be made from recycled materials. He questioned the potential of a fake or simulated sculpture. He titled his works as if they were solid bodies, winking at his audience, aware in turn that they were empty volumes. He used natural elements like earth and water along with construction materials like asbestos, and divided his seas and fields into modular units. He brought into the studio new consumer products and synthetic fabrics to create animals, traps, and bridges. And while the complexity of his approach to sculpture is indisputable, the factor that makes his artistic practice so brilliant and original is another. Pascali is a timeless artist because he was an exhibitionist: he understood that post-war artists had to devote as much energy to exhibiting as they did to refining works in the studio. Being an exhibitionist meant, first and foremost, creating engaging yet temporary environments with one’s works, environments that were more than the sum of their parts. Secondly, the exhibitionist had to seek out as many exhibition opportunities as possible and then take control of them. Thirdly, the exhibitionist recognized the importance of having images of the exhibition before and after setup. Fourthly, the exhibitionist had to breathe new life into their work for each exhibition, radically changing their approach to realizing each exhibition project. All these elements are traceable in Pascali’s dazzling career.

“What I do is not a search for form. It’s a way of verifying, starting from another point of view, what others have already done. A way of verifying my world by comparing it to others.”

The rooms that simulate the original spatial dimensions of the galleries where Pascali exhibited allow visitors to experience the unconventional display methods used by the artist. These volumes reconstruct the environments created for his first solo show at Galleria La Tartaruga (Rome, 1965) with two series including, on one side, Primo piano labbra and La gravida or Maternità, and on the other, Colosseo, Ruderi sul prato, and Muro di pietra. The exhibition at Galleria Sperone in Turin in 1966 is presented with the series of Armi, and those for Galleria L’Attico in 1966 and 1968 with the series of Animali, Botole or Lavori in corso, and wool sculptures, including Trappola. The works for the solo presentation at the Art Biennale (Venice, 1968) include Cesto, Contropelo, Pelo, Ponte levatoio, and Solitario. The second section is dedicated to the natural and industrial materials used by Pascali, delving into their origin, their commercial use, their use by other artists, and their transformation over time. Visitors move through different areas, each focusing on a specific material such as canvas, dye, earth, asbestos, synthetic fur, steel wool, foam rubber, car parts, hay, and brushes. The third section winds through the North Gallery and testifies to Pascali’s fundamental contribution on three crucial collective exhibitions: Fuoco Immagine Acqua Terra, Cinquième Biennale de Paris: Manifestation Biennale et Internationale des Jeunes Artistes, at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (Paris, 1967); and Arte Povera curated by Germano Celant at the Galleria de Foscherari (Bologna, 1968). In the South Gallery, the fourth section investigates the ways in which Pascali appeared alongside his sculptures in historical photographs taken by Claudio Abate, Ugo Mulas, and Andrea Taverna, and in the 16mm video SKMP2 (1968), directed by Luca Maria Patella.

For further information fondazioneprada.org.