Happy Gas is definitely a unique opportunity to investigate an entire original corpus of art that is distinctive and provocative in subverting notions of gender, sexuality and identity. Indeed, Sarah Lucas is internationally renowned for her irreverent way of making art, her practice bluntly reworking the boundaries and limits of contemporary society, reworking a vision that is more than courageous and fascinating. There are more than 70 works on display at the Tate, ranging from early sculptures born out of his attendance at Goldsmiths College, to more recent groundbreaking photographs and newly completed works. Lucas is a London-based artist who rose to prominence as a member of Young British Art, a famous group of visual artists of the early 1990s who came to prominence on the London scene in 1988 with Freeze, staged in an abandoned warehouse and curated by Damien Hirst alongside his later colleagues Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, Gary Hume, Angela Bulloch and Jenny Saville. The aim to astonish, provoke and even disgust by creating glimpses of contemporary social and political realities does not seem to have been contradicted; on the contrary, Happy Gas seems screaming even louder messages of inclusiveness and revolution.

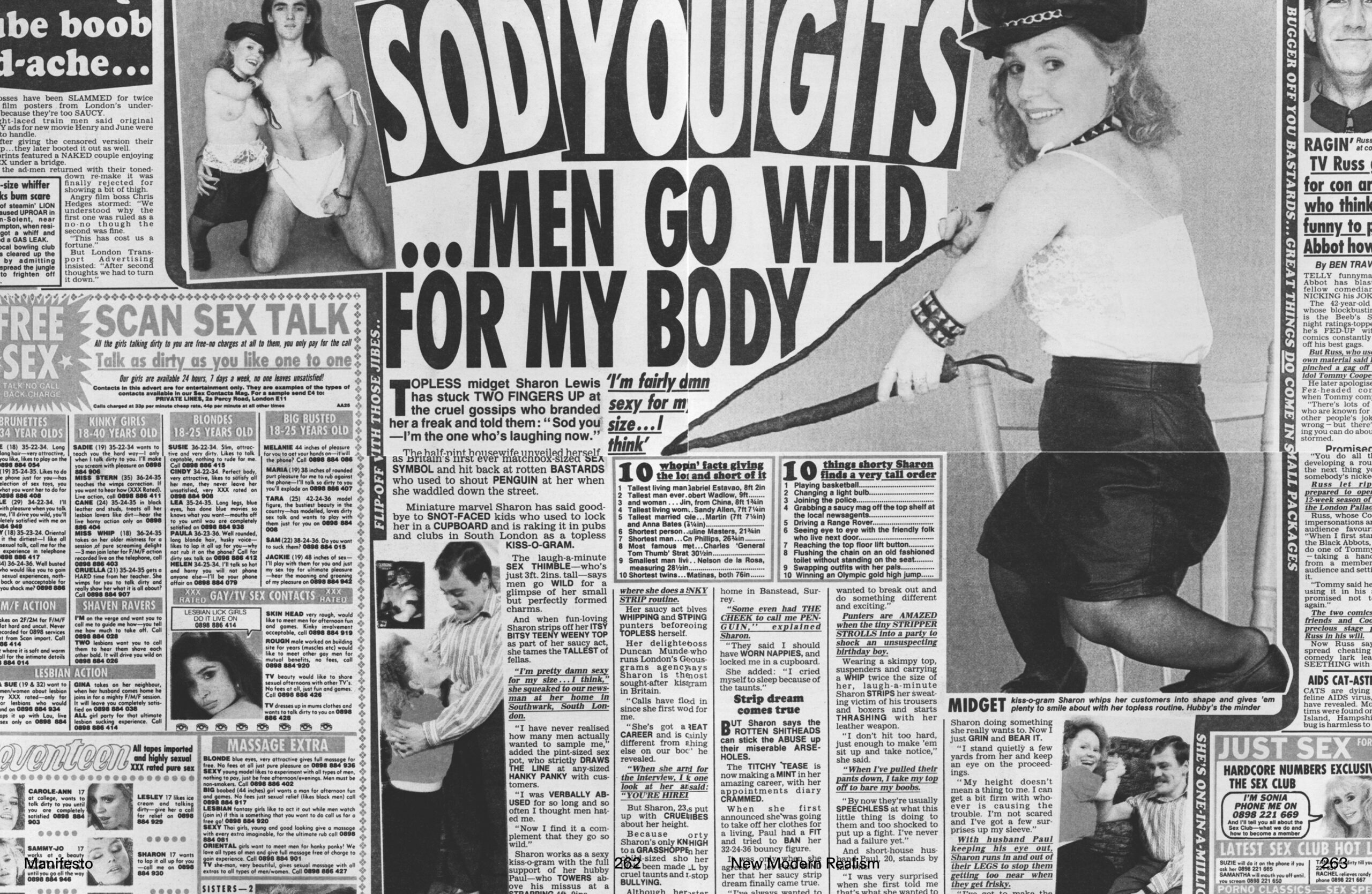

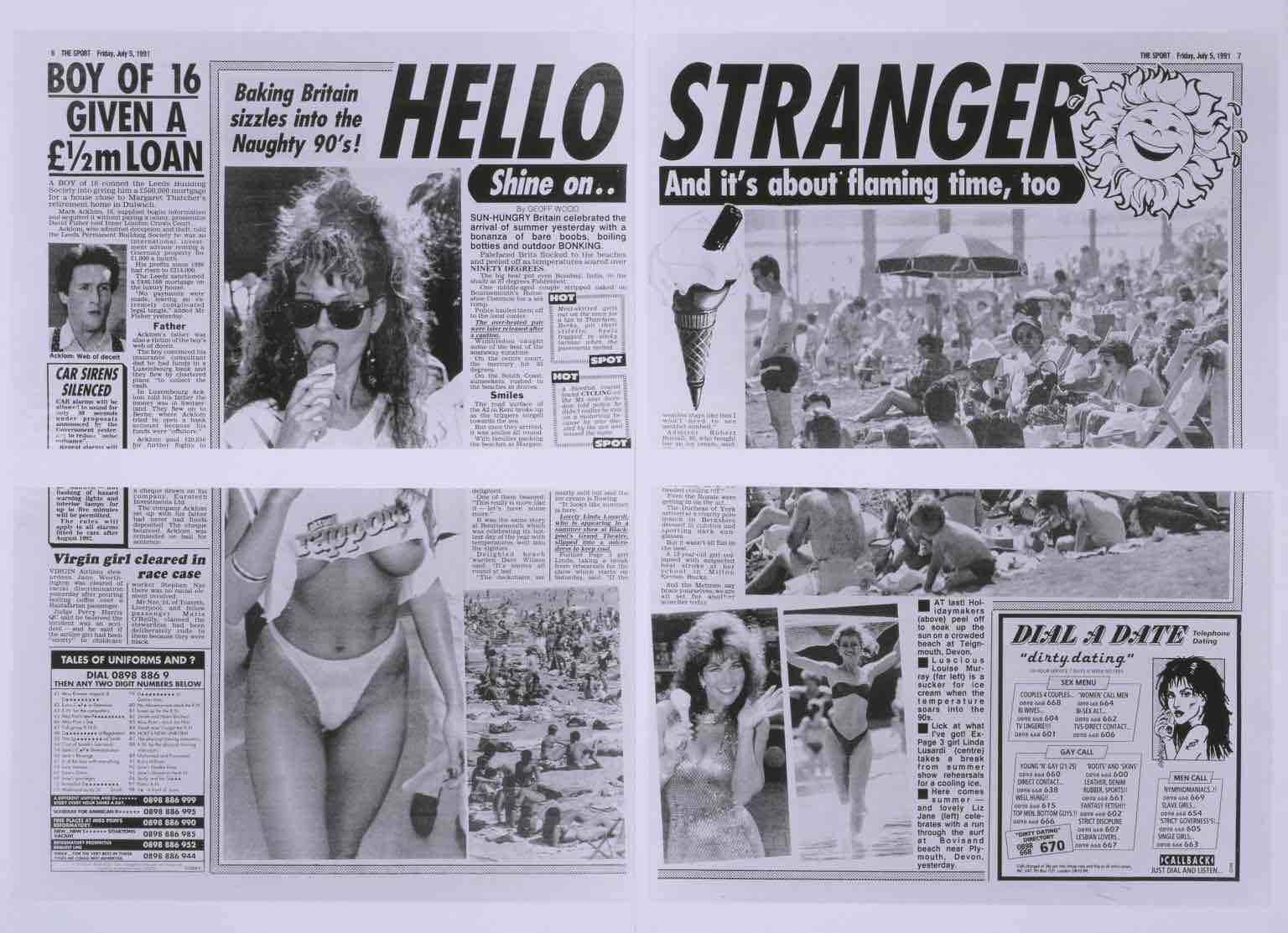

In this exhibition the socio-cultural upheavals declining in a visual and poetic dialectic are designed to highlight new issues: Sarah Lucas’s sculptures want to impose themselves beyond the gaze, to freeze thought by presenting us with precariousness and dismay, disruption and subversion. The Tate Britain exhibition opens with some early works, including those made from newspaper collages such as Sod You Gits 1990 and Fat, Forty and Flabulous (1990). These are works that introduce the use of innuendo and puns, as well as her interest in feminist discourse and representations of the female body. There will also be glimpses of her childhood, reinterpreted in the light of her success, highlighting her continuing efforts to examine social conditions beyond the confines of the art world.

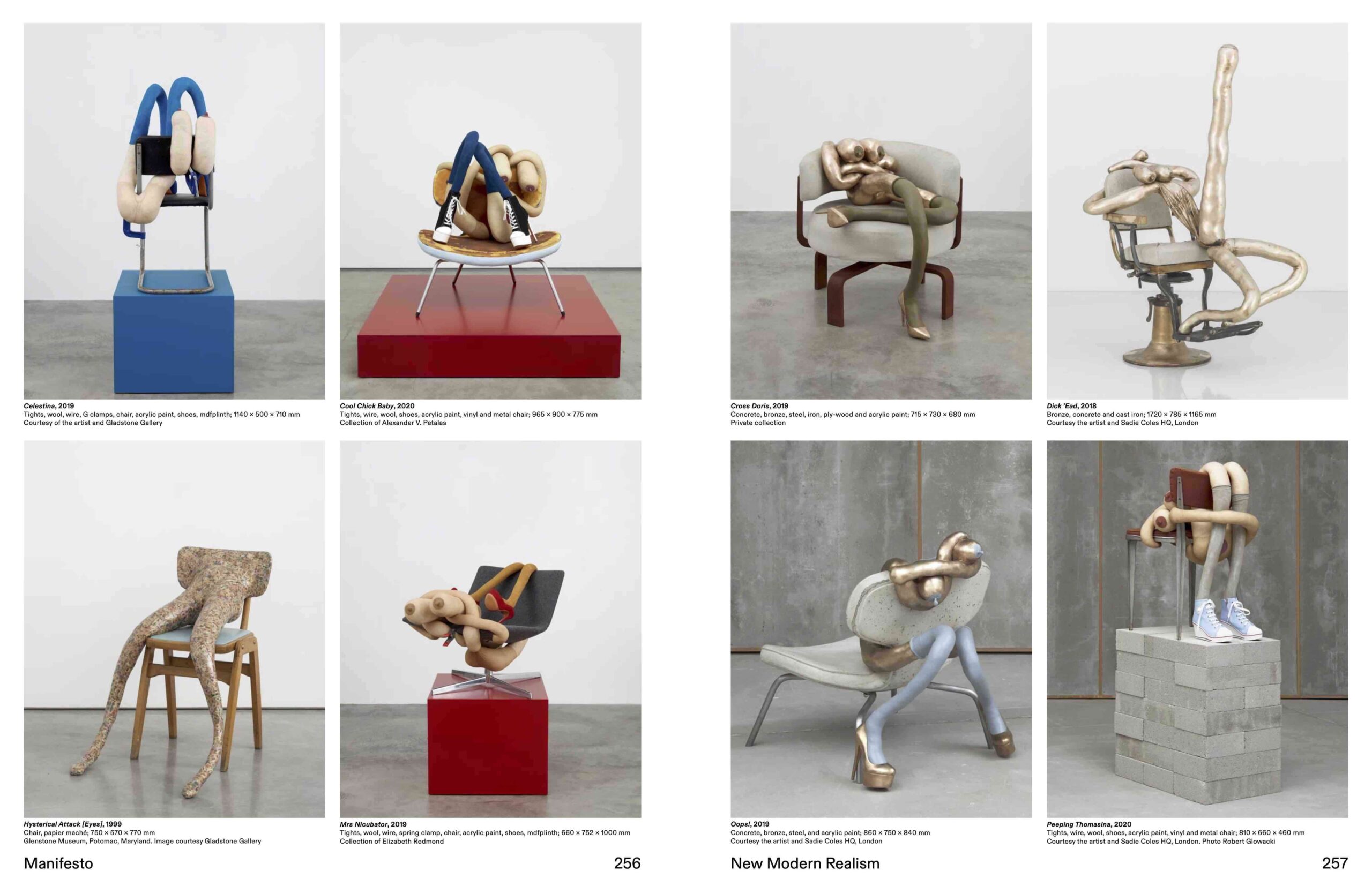

“I decided to hang the exhibition mainly on chairs. Much in the same way that I hang sculptures onto chairs”

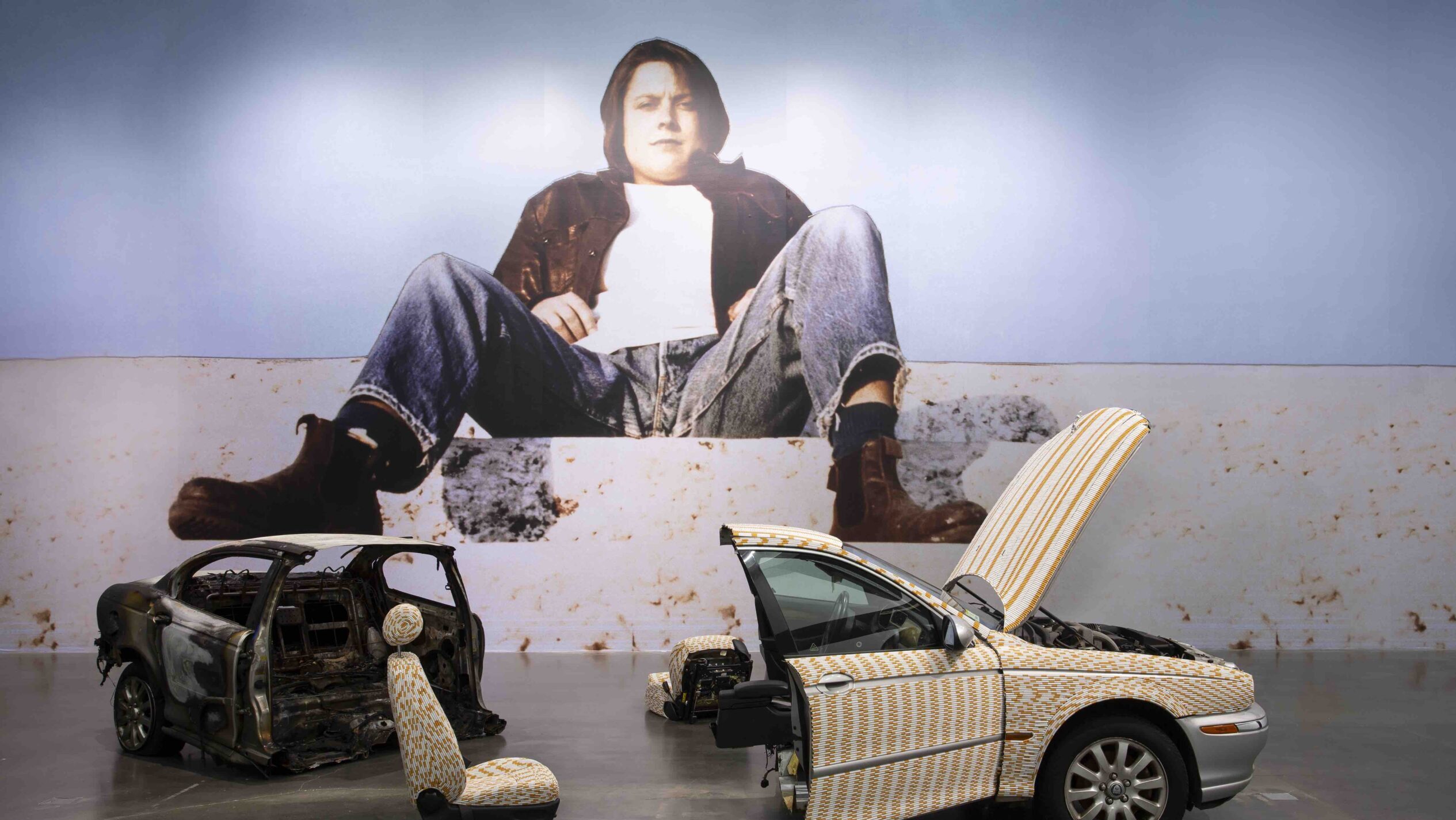

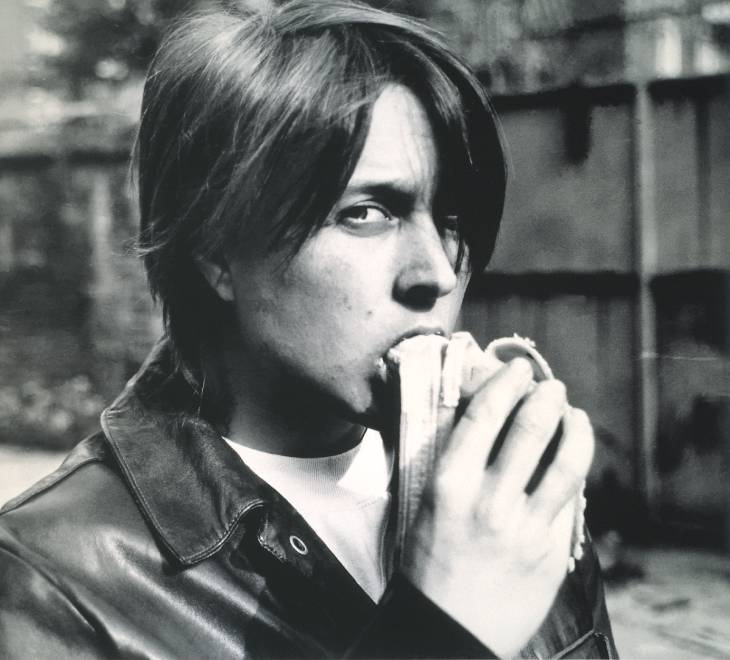

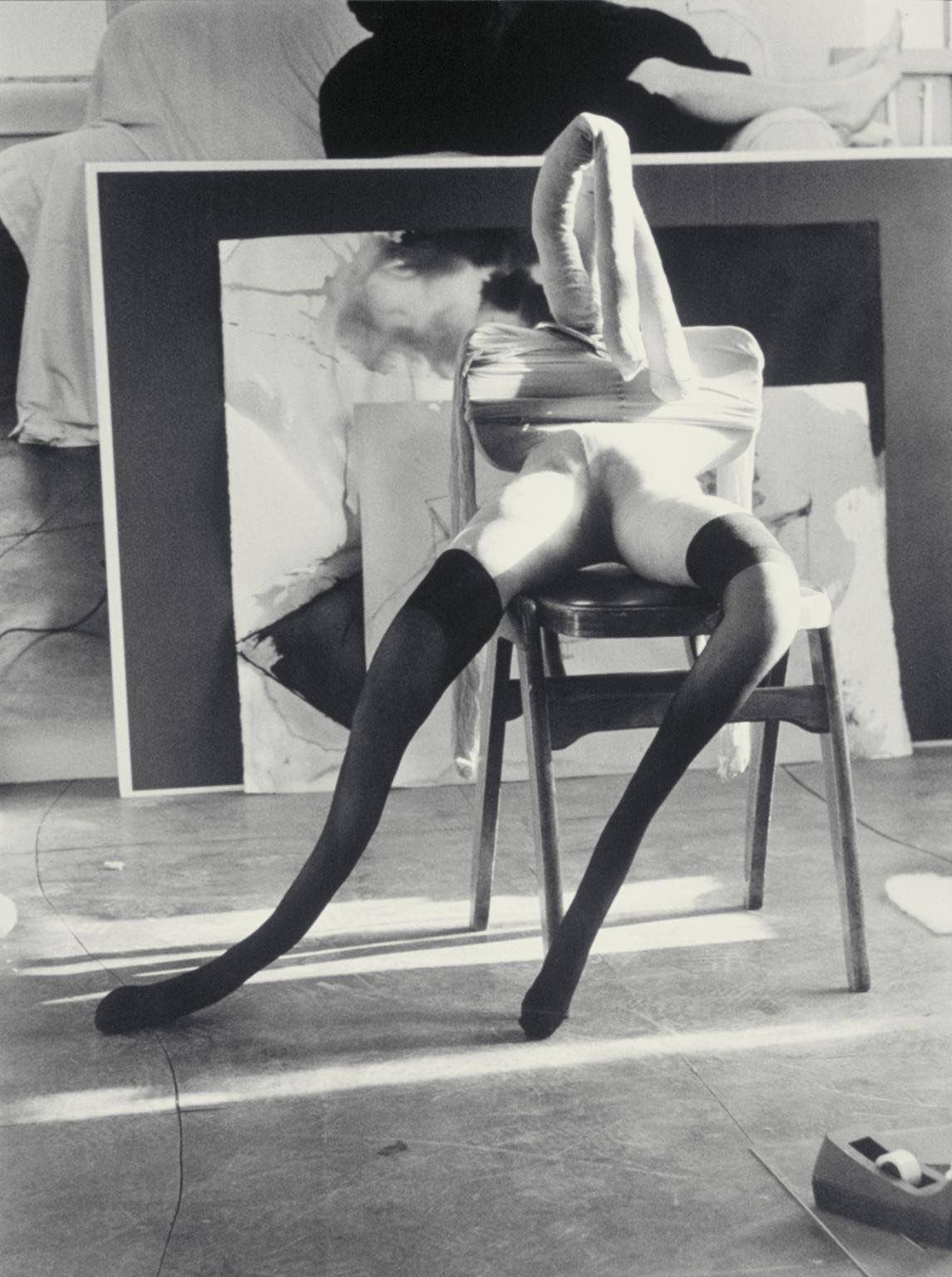

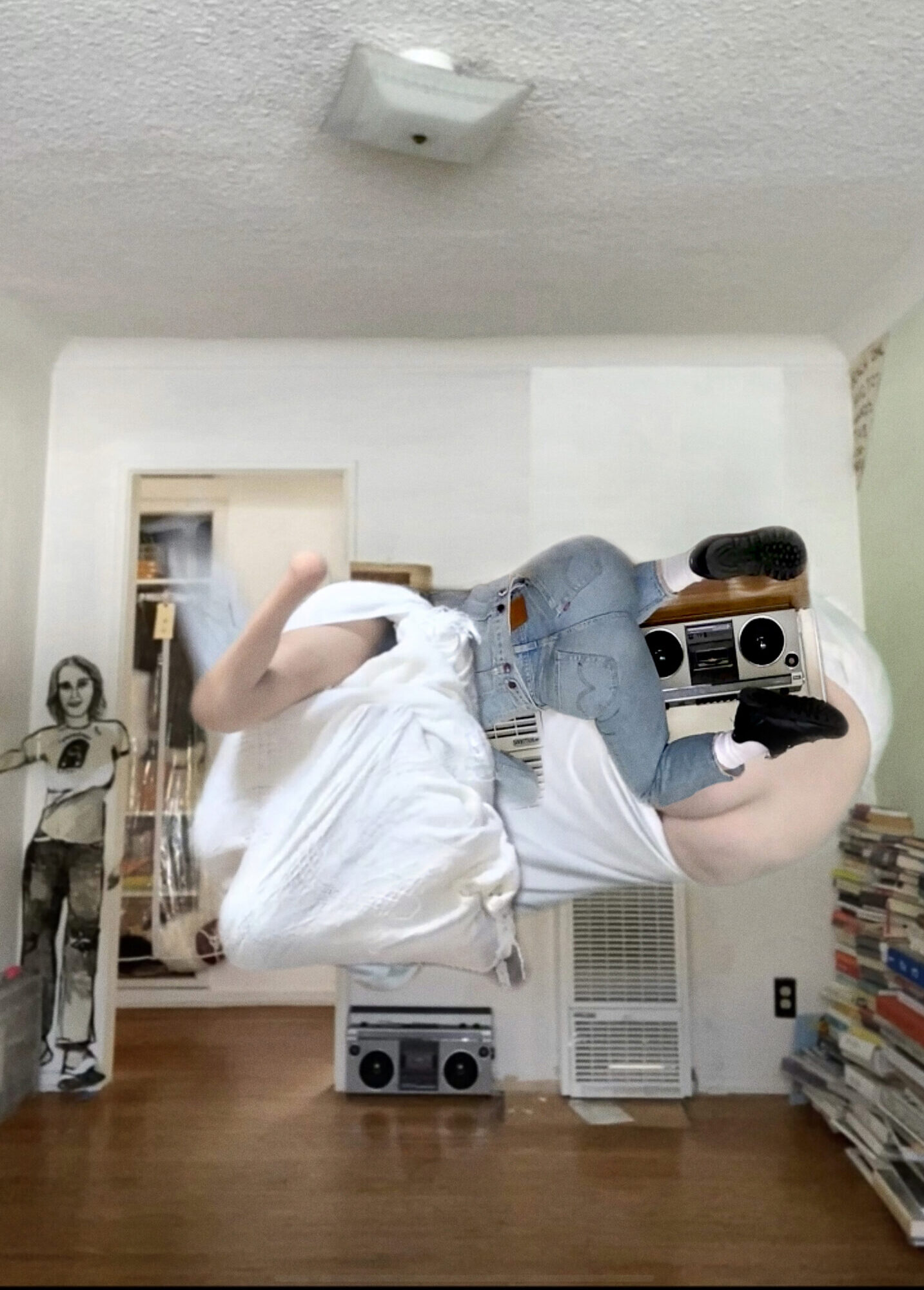

Lucas’ famous Bunny series – first conceived in 1997 – features the artist’s most evocative works, female nudes reclining on chairs, or ‘muses’ as she calls them. Headless, contorted, endowed with exceptionally long limbs and multiple breasts, they participate in the deconstruction of a patriarchal imaginary, where the female nude is a critique of its own objectification. The most evocative works will be juxtaposed – in the halls of the Tate – with photographs documenting his entire career, including his first and best-known portrait Eating a Banana 1990. These series explode as backgrounds and look down on sculptural works, reflecting the important role of the photographic image in Lucas’ practice and establishing a dialogue between his older and younger selves. This dialogue between contrasts is also seen in the arrangement of the entire space: the effect is an irregular symmetry, emphasised by the cross-shaped wall that frames and organises the sculptures, negotiating the rhythm of the viewer’s gaze.

“The power is in the power of the thing, not in me trying to be aggressive or being one way or the other. It gave me a kind of strength.”

And then plaster becomes the protagonist with the series composed by Pauline, Sadie and Me (Bar Stool), brought together ‘cause having been shown for the first time in 2015 when Lucas represented Great Britain at the 56th Venice Biennale. A highlight of the exhibition is the large series of recent works made between 2019 and 2023, including ten works that are being shown for the first time. Some show a return to the street-found objects and padded tights of Lucas’ early works, such as SUGAR 2020 and CROSS DORIS 2019, while in others she approaches new materials, such as bronze and resin. The British artist’s recent works show how she has continued to rethink the themes that have defined her career, including the objectification of the female form and the anthropomorphic potential of everyday objects, constantly bringing new perspectives to her practice, but most importantly not letting down that humorous and unnerving honesty about desire to which she had accustomed us. Happy Gas is a necessary artistic study of the poetic diary of Sarah Lucas’ sculptural work.

For further information Tate.org.uk