HANS ULRICH OBRIST IN CONVERSATION WITH MENELAOS KARAMAGHIOLIS

HUO I want to ask you to tell us about how it all started, how you came to film, how film came to you… I’m also curious to know who inspired you.

MK The stories of the others have always been an effective way for me to live a meaningful life. I started thinking of cinema ever since I can remember myself, while reading literature and trying to animate those stories with images. As the youngest child in my family, I used to steal the books of my siblings. At the age of 10, I had already access to The Marquis de Sade and other erotic libidinous stories. And then, I would try to imagine and create my own moving images with a cast borrowed from films, magazines and people I had met and had made an impact on me. Right after the fall of the dictatorship, I would listen to my siblings analyzing the films by Pasolini, Bergman and Angelopoulos for days. And I started dreaming cinematically in a time when it was difficult to make cinema in Greece. That is why Angelopoulos and all those pioneers were important; because there was no film industry or solid film education here. In the ‘70s and the ‘80s, it took strength to decide to make experimental cinema or films d’auteur in Greece. Those filmmakers had been very active politically against the Junta of the Colonels and they changed all the stylistic and formalistic choices of cinema. During the ‘70s, they travelled in festivals abroad, but the Greek audiences could not find their films in local theaters, especially in my hometown. When I convinced my parents to let me move to Athens alone, at the age of 14, I found a cinema where I could watch arthouse films every day. In this new city and life, I started realizing that in Greece there are so many stories, ancient or contemporary, that could feed cinema and any kind of moving image in a strong way.

HUO You went to Athens when you were 14, and you mentioned that you met all the people you had dreamt of meeting. Can you talk about these encounters?

MK As a teenager, I used to spend the holidays in my hometown, where I would work in a gas station, in a butcher’s shop, and many other places all day long. While waiting for the next customer, I used to read a fancy magazine of the time and its interviews of some remarkable people that I wished to meet. I met most of them by chance. In Athens, there are no clear boundaries between neighborhoods and social classes. As I lived alone, I had enough freedom to discover the city pretending to be an adult. Vassilis Vassilikos, the writer of Z, that Costa-Gavras shot in the homonymous acclaimed film, became a good friend when I was 18, and still is. It was him who initiated me to the magic world of film writing, as he was also a good screenwriter. He introduced me to people I couldn’t imagine I would ever meet: Milan Kundera for example or Jorge Semprún. At the time, they met every first Monday of every month, in the secret back room of a bar, in Paris, that was separated from the front room with a curtain. That’s how I met important intellectuals from all over the world that treated everyone equally. I had the opportunity to meet my idols at a very young age; that created new values that lead me towards the real remarkable people: the antiheroes that give me the strength to define my art in a more essential way.

“All my works are based on true stories, I couldn’t do otherwise. This approach gave me all the variations of the themes and topics I needed, and even the ability to formalistic experiments.”

HUO We see a journey where you begin with a kind of documentary style, you stopped making documentaries and there is a whole period in your life where you were anti-documentary and you made successful fiction and feature films. Then, there is a return in a very different way to the documentary. I want to hear more about this journey because I think it’s so fascinating.

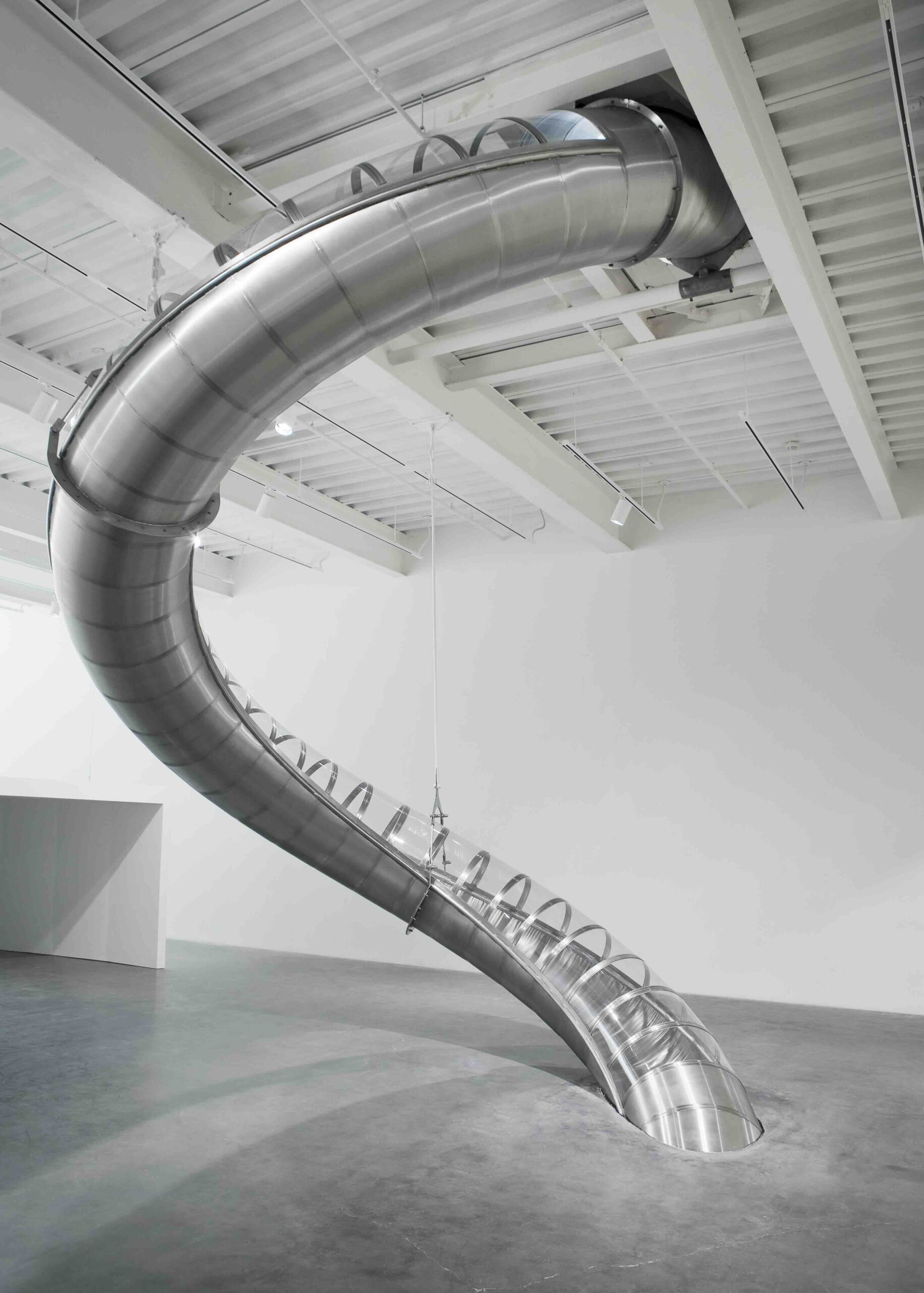

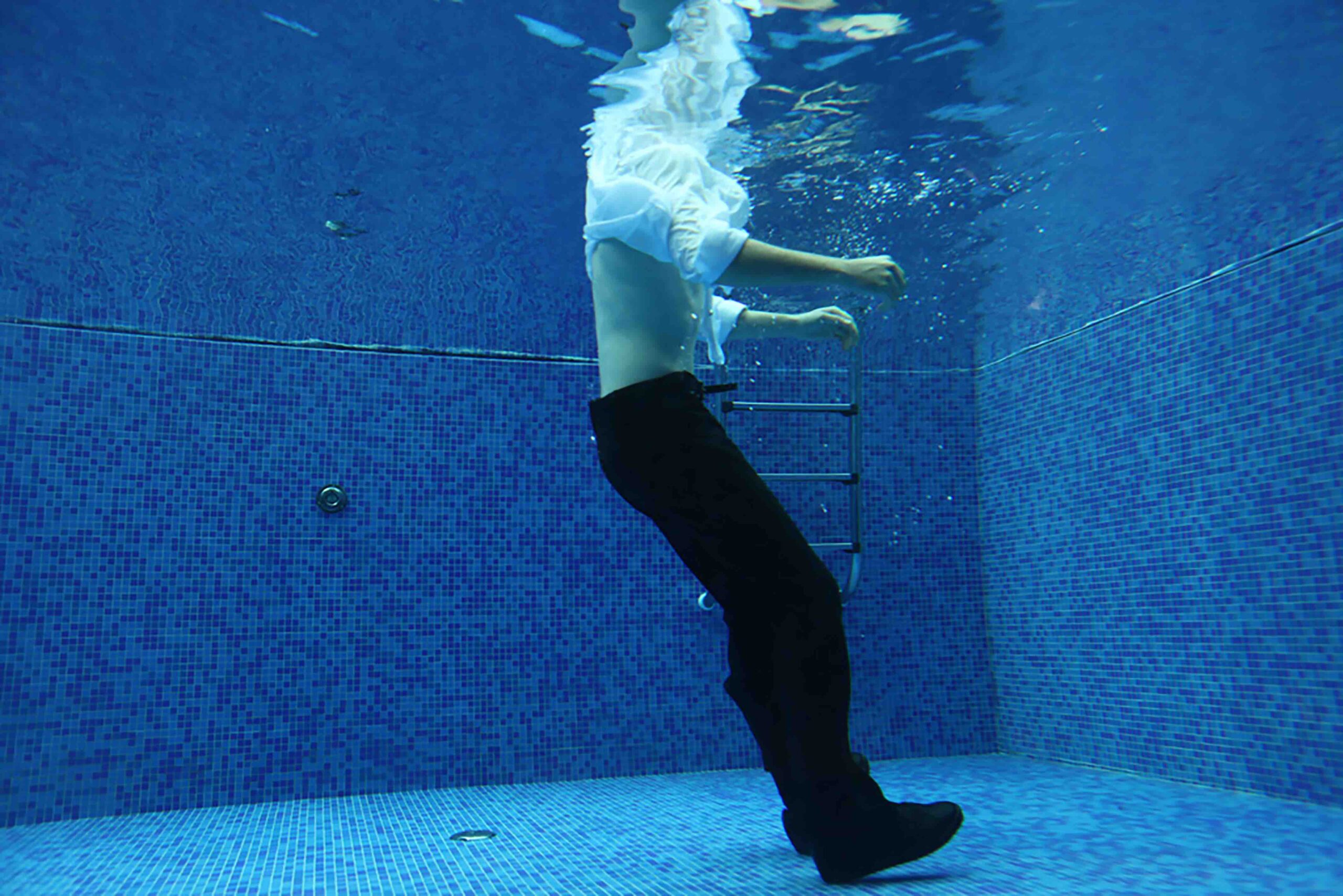

MK All my works are based on true stories, I couldn’t do otherwise. This approach gave me all the variations of the themes and topics I needed, and even the ability to formalistic experiments. Now, using this new digital world in every possible way, I started filming by myself after 2011, and creating a new relationship with document for the art I envision. That’s why the team I belong to is called Døcumatism: I feel that we have to go further on what is the real power of document and how document can motivate and inspire art. It has been a few years now – due to the endless crisis in Greece – that we are surrounded by intense stories and images that have offered a new impetus to documentary films and that’s something one can see very clearly in the works of young filmmakers and artists. During the last ten years, I felt that no fiction could depict with precision these inspiring stories that happen around us, without distorting them, but their real protagonists.

HUO Can you tell us a little bit how this Døcumatism evolved? It’s a movement, so movements usually have an own manifesto and I was kind of wondering if there is one. How is Døcumatism concretely organized and are you the instigator or the catalyst, in a way?

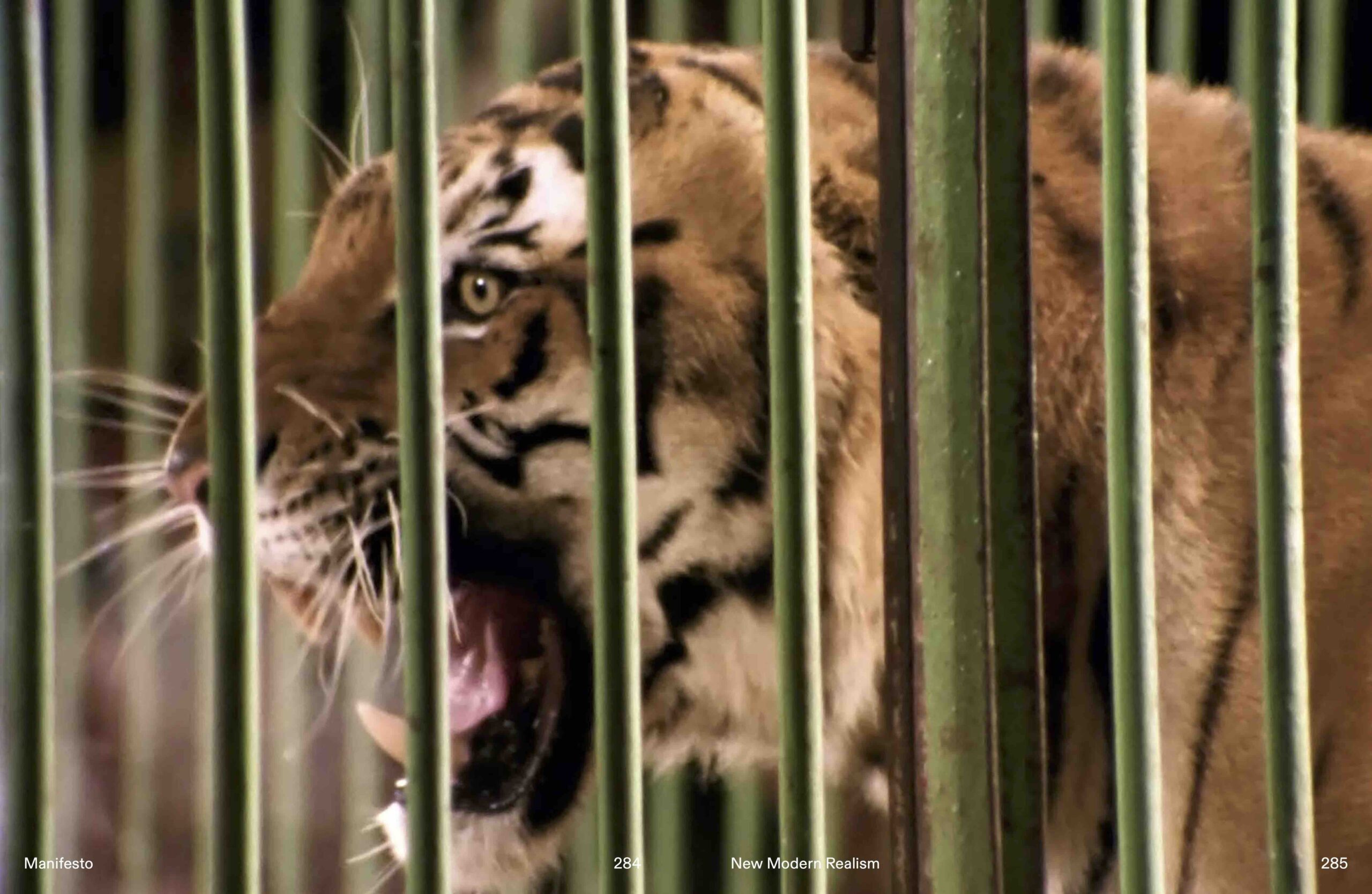

MK I am scared of any kind of proprietary or egocentric relationship in teams and works of art. I believe in encounters with people, I do interviews with them and then starts a relationship that gives birth to collective works of art. The structure of Døcumatism started from the need to not distort reality, and was shaped by the course or the evolution of the works themselves and the needs of its members. It started as a play with Malevich’s suprematism. 100 years ago, it told us to set our imagination free to create. In our century, we all felt that the document is crucially present on the news, on our screens, but at the same time it is used in an abusive way. So, could there be a new way to search further on how we can use the document as a starting point that sets imagination and creativity free, without imposing a boring or limited representation? Through all those actions that were based on moving image and documentary, we met people – whom we rarely meet or avoid to meet – who felt the need to be given the opportunity to express themselves, to try to find solutions for their crucial social problems and restrictions; as well as to cancel the dangerous intrusiveness of the lens in their lives, while turning it into a supportive tool. I think these are the most creative people I have met over the years. And art is a very brief and interesting way to express yourself with a meaningful political way. During the process, we discovered that moving image can be a starting point for important actions, meetings and awakening; also, moving image is a concise language that can reveal the truth and lead to a free expression that does not impose just a realistic representation.

Read the full interview on Muse September Issue 62.