Hans Ulrich Obrist in conversation with Barbara Kruger

HUO Let’s begin at the beginning: how did art come to you, or how did you come to art?

BK I didn’t really come to art, because until I was quite a bit older, I wasn’t sure what art was. I only went to art school for about a year and a half; I have no graduate degrees. Being an artist was certainly not in my realm of possibility growing up in Newark, New Jersey. I did think of the idea of being an illustrator or a commercial artist, but an art world was something I couldn’t even imagine. And art really didn’t come to me either. As I’ve said many times before, when I was first starting up, the so-called art world in New York, in terms of power, was 12 white guys in lower Manhattan; there wasn’t really room for anyone else. Although artists of many genders and many colours did exist, they weren’t part of that hierarchy. It seemed like a forbidden terrain.

HUO Can you tell us about the artists, architects and thinkers that influenced you at the beginning?

BK What had always been of interest to me as a young person, before I was an artist, was the built environment and architecture. That was always a fascination of mine and I think maybe I had dreams of becoming an architect, but that never happened. I really hadn’t gone to museums much at all. My parents took me to MoMA in New York once when I was young. What I remember most from my visit there was the design department, all the great objects, commodities, architecture and design solutions. That’s really what I took away from it.

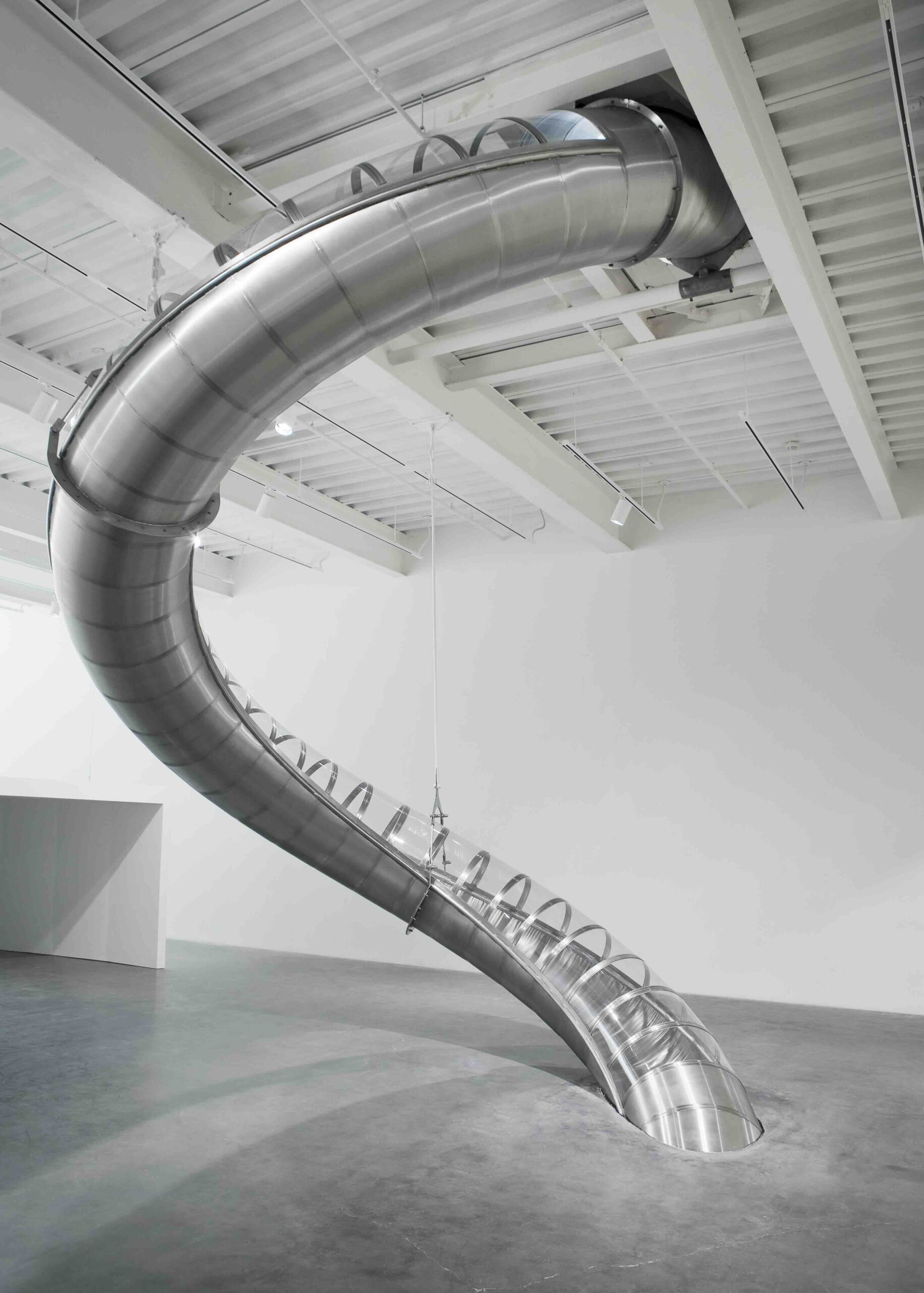

HUO You once said that “architecture is one of the predominant orderings of social space”, and also that just by “entering it, you become part of it”. Were there any specific architectural experiences that inspired you?

BK Not so much. The interesting thing, in terms of residential architecture, is that my parents never owned property; we never owned a house or apartment. Sometimes we spent weekends – these dream journeys – going to open houses and fantasising about what it would be like to live in these properties. I remember all the rooms had velvet ropes at the entrance, so you couldn’t walk into them. It was my experience of not being allowed within the privacy of that residential space. I remember drawing plans for housing developments with differing models of houses as a young girl. It was such an unreal thing for us to live in anything but a three-room apartment in Newark. I saw it as a fantasy projection. One of the interesting things about moving to Los Angeles 32 years ago is that I was very aware of the history of the modernist architecture from 1917 to 1970 here in Los Angeles. The expatriates, the émigrés from Germany and Austria created such amazing lived environments and built environments.

HUO So these drawings of developments are some early unrealised architectural projects of yours.

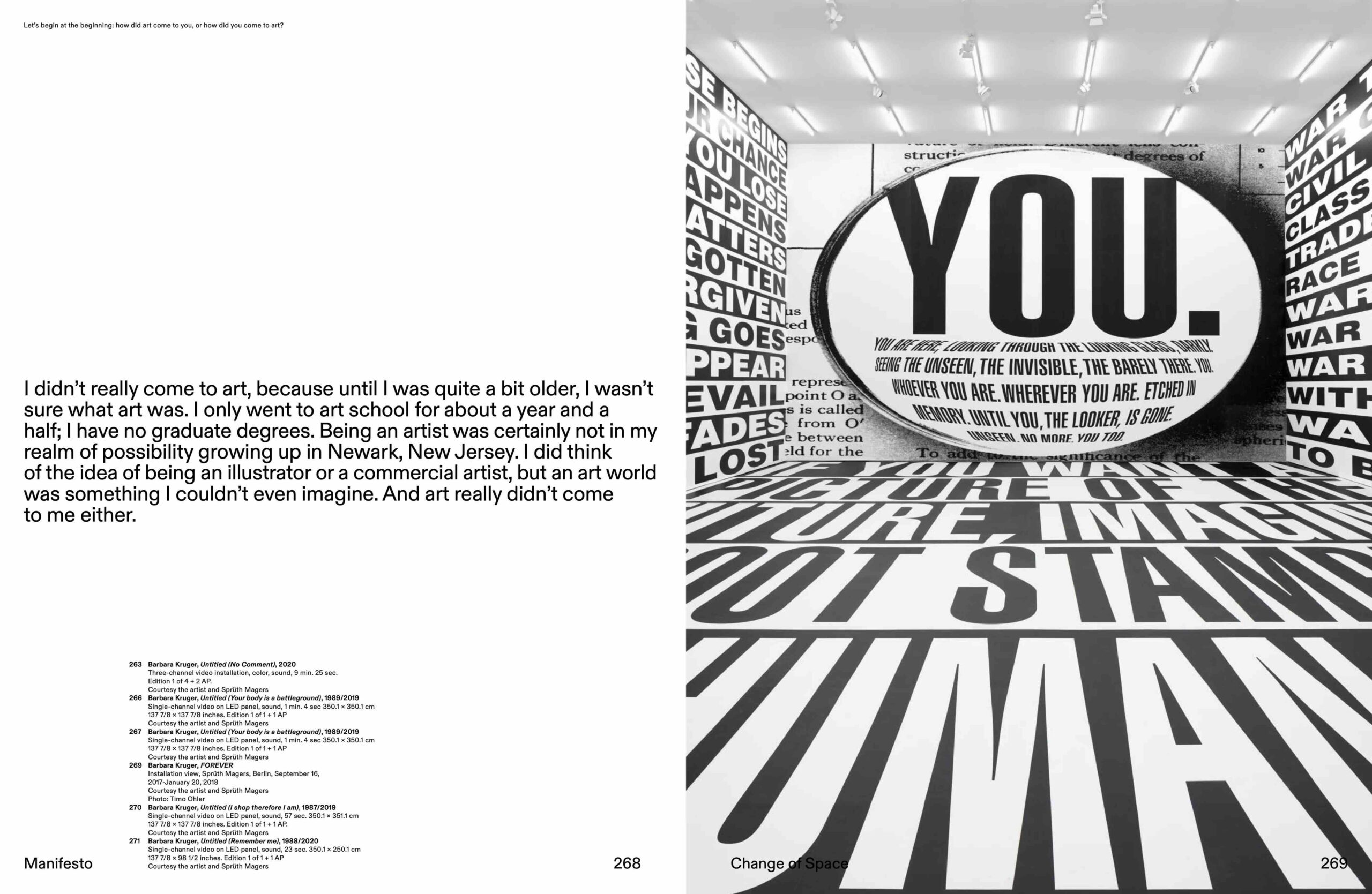

BK Yes, but, in truth, when I was able to do installations of the scale that I’ve been doing for the past 20–25 years, it was a chance for me to exercise that thrill in problem-solving. I don’t make models or anything like that – when I walk into a space I pretty much know how I want to engage it and how I choose to spatialise the meanings of my work. It’s always an incredible challenge and pleasure.

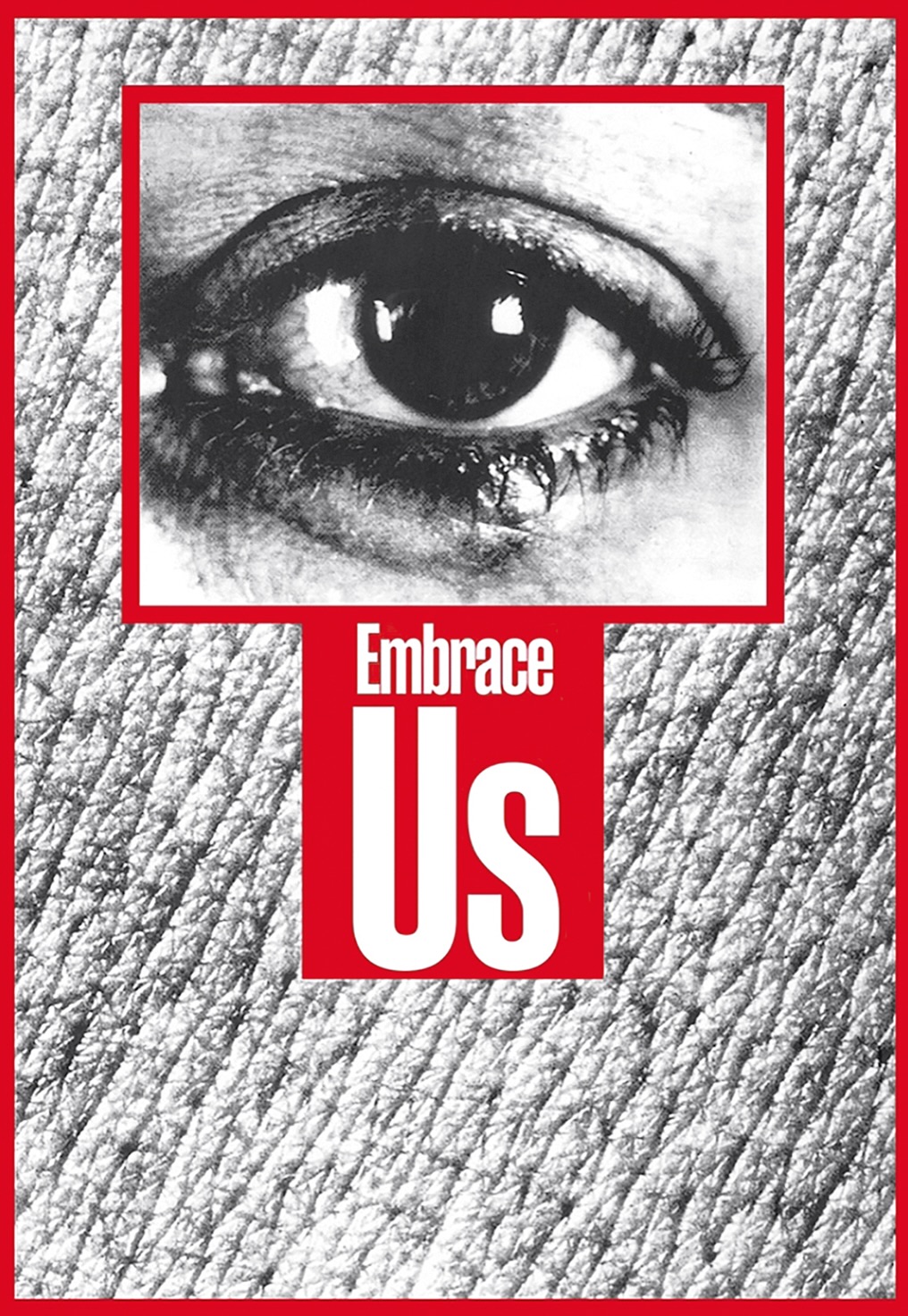

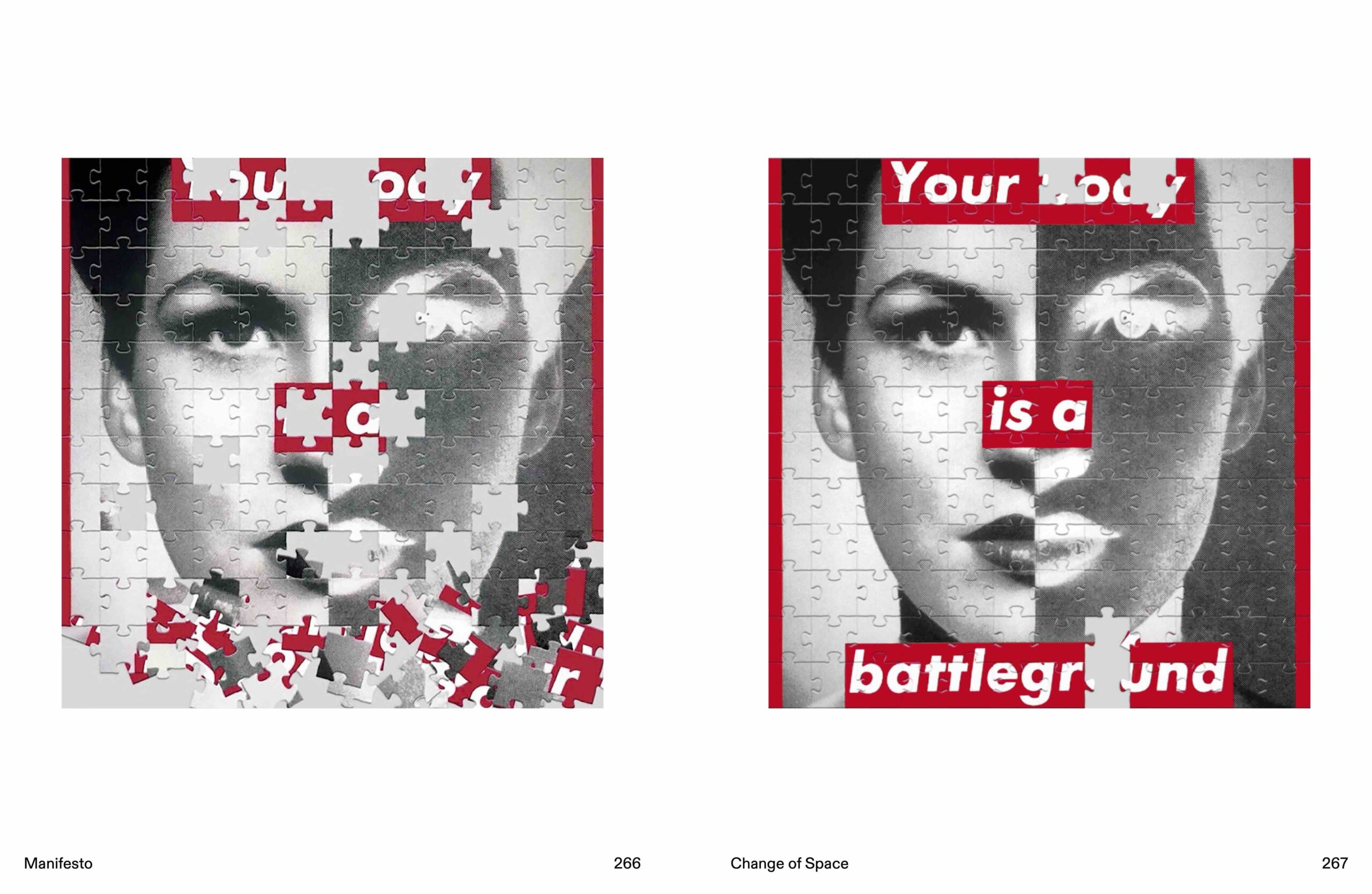

267 Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989/2019. Single-channel video on LED panel, sound, 1 min. 4 sec 350.1 × 350.1 cm 137 7/8 × 137 7/8 inches. Edition 1 of 1 + 1 AP. Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers.

HUO That’s beautiful. It’s interesting also that your beginnings were as a graphic designer and picture editor. Your starting point wasn’t the art world, but graphic design. You got a job at the Condé Nast magazine Mademoiselle and figured it out day by day. It’s similar to my experience: since I never studied curation or exhibition-making, I just started and then every day figured it out somehow, in a DIY way. You said that the visibility of type and its possible meanings were relevant for you from the very beginning. Can you talk a little bit about how your work grew out of this very day-by-day practice?

BK That’s a very important point. One thing that you and I share is the fact that we entered our professions before they were so professionalised – you didn’t need a MFA or PhD in curation to be an artist or to be a curator. You could follow your desire on a certain level. Things have changed to quite a degree, but for me, getting these design jobs at magazines was a way of supporting myself in New York without an inheritance. I had no income, no money to fall back on. It was a time when I had fixed up three very funky lofts. I never owned a loft in New York. I could never afford it, unfortunately. But while I was doing that, I got these freelance jobs, the last of which was with Condé Nast. I worked at Mademoiselle and got paid almost nothing – it was the kind of prestige job that in theory should be paid well. Nevertheless, I learned a lot on that job and I developed my fluency in working with pictures and words. I feel so fortunate that it came to me so organically – I wasn’t schooled in it, and I don’t know the ins and outs of fonts and design history, but I approached it visually. It was something that I learnt through doing.

HUO What would you say is the number one work in your catalogue raisonné, when you found your language?

BK I can’t even say. I spent so little time as a student that I consider the initial work that I did when I was living in Soho and working at Condé Nast and starting to do stuff in the studio, as my student work. I didn’t have an education experience or access to the different menu of styles to pick from, which happens when you go to art school. I just had to figure out what it might mean to call myself an artist – I needed to understand what really engages me. I had to figure out what really struck a match in me, rather than just a stylistic choice that would become my art.

Read the full interview on Muse February Issue 63.

This is an excerpt from a conversation commissioned by Serpentine on the occasion of Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You., Serpentine South, 1 February – 17 March 2024 and edited by Natalia Grabowska. Read the full interview in the free exhibition guide available at Serpentine.