Born in 1954 in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, Cindy Sherman has spent over forty years exploring a vast array of themes related to representation and personal identity in the era of contemporary media. Rising to prominence in the late 1970s within the Pictures Generation alongside artists such as Sherrie Levine, Richard Prince, and Louise Lawler, Sherman first turned her attention to photography while studying at Buffalo State College. In 1977, shortly after moving to New York, she began her series of Untitled Film Stills. Here, Sherman continued to transform and reconstruct familiar figures from the collective psyche, often in unsettling ways, and by the mid to late 1980s, the artist’s visual language began to explore the more grotesque aspects of humanity through the lens of horror and abjection, as seen in works like Fairy Tales (1985) and Disasters (1986-89). Her photography moved away from the forced pursuit of beauty: in these representations, Sherman introduced deliberately visible prosthetics and mannequins into her work, details reused across series like Sex Pictures (1992) to add layers of artifice to her constructed female identities. The contrast between appearance and reality is pushed to extremes, calling on the viewer to play an active role in defining what they are confronted with.

“When I’m shooting, I try to reach the point where basically I don’t recognize myself anymore. Often, that’s exactly the point.”

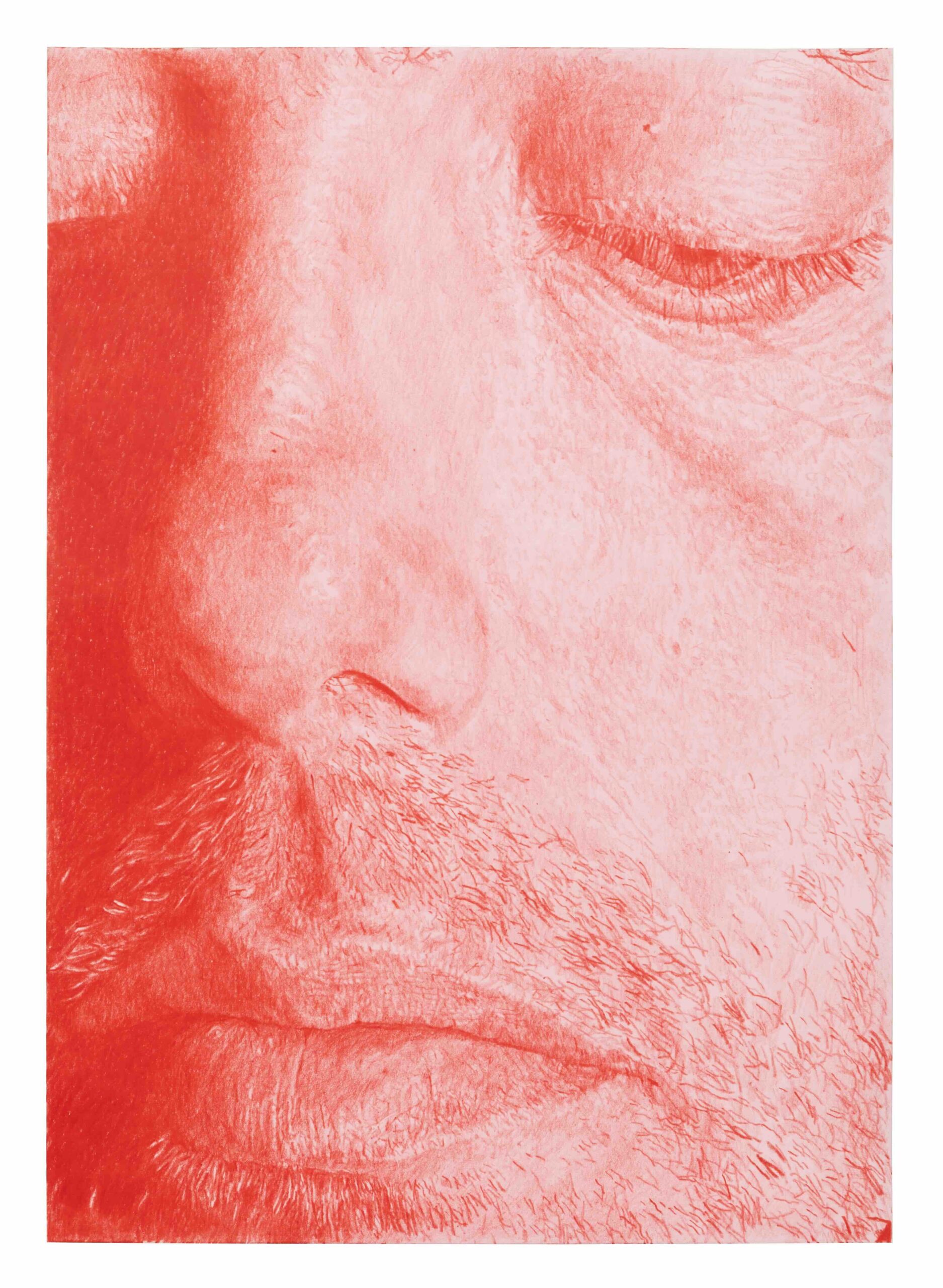

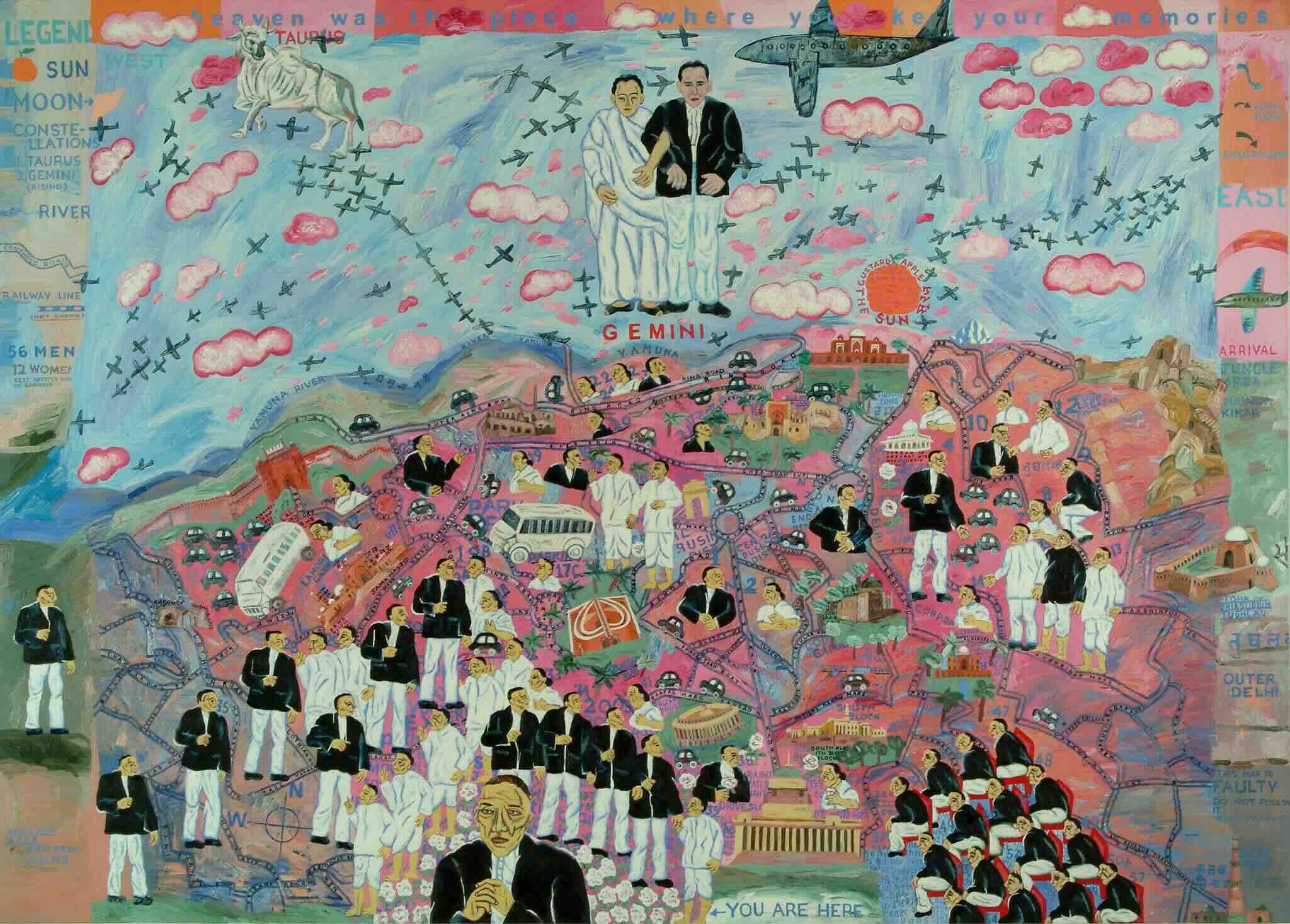

Starting from the early 2000s, Sherman has utilized digital technologies to further manipulate her characters: in the Society Portraits project (2008), for instance, she employed the use of a green screen to recreate the sumptuous environments typically frequented by high society women. These CGI backgrounds add a charm to Sherman’s women akin to much more universally recognized works of art, made up and immersed in their social status, while facing the awareness of aging. In 2017, the artist began sharing her portraits on Instagram, modified using apps and filters for facial alteration, once again transforming into a variety of kaleidoscopic characters. The disorienting and unsettling posts to the audience serve to underscore the dissociative nature of social media compared to reality: Sherman primarily transforms into affluent middle-aged women at the height of power but subject to physical decline. Despite their attire acting as a protective shield, they are completely exposed to the camera and those who scrutinize them up close. In her most recent works, Sherman has constructed collages by assembling photos and images depicting parts of her own face to build entirely new characters, using digital image manipulation to emphasize the malleability of the self. By removing external context and foregoing any mise-en-scène, she focuses solely on facial and head details.

“We’re all products of what we want to project to the world. Even people who don’t spend any time, or think they don’t, on preparing themselves for the world out there – I think that ultimately they have for their whole lives groomed themselves to be a certain way, to present a face to the world.”

In these works, Sherman combines a series of digital techniques that incorporate both black and white and color photographs, alternating with more traditional methods of transformation, such as makeup, wigs, and costumes, to create true caricatures of women laughing, screaming, crying, and posing before the viewer: although all the images are actually composed of the same person’s face, they appear as ordinary portraits; despite their layers, Sherman’s final works give the true impression of individual subjects comfortably seated in front of the camera. The women manufactured by Sherman interrupt the voyeuristic gaze of subject-object associated with the most established traditions of portraiture, and in the dual role of photographer and model, she continues to overturn the typical dynamics between the artwork and the artist. This effect is amplified in works like Untitled #632 (2010/2023) and Untitled #654 (2023), where Sherman combines sections of both black and white and color faces, highlighting the presence of the artist’s hand and disturbing any perception of reality, while reminding us of her early hand-cut color and black-and-white works from the seventies. Using this layering technique, Sherman creates a place of multiplicity. Photography begins to be increasingly seen as closer to painting, but not only that: it draws our attention to the fact that identity is an infinitely complex and often constructed human construct, impossible to conceive in a single form.

For further information hauserwirth.com.