Tracey Emin: I followed you to the end

White Cube Bermondsey, London

19 September – 10 November 2024

Tracey Emin returns to White Cube Bermondsey with the exhibition I followed you to the end, a presentation of new paintings and sculptures that traverse love and loss, mortality and rebirth. A British artist known for using a wide range of media, including drawing, video, installation art, sculpture, and painting, her works are confessional, provocative, and transgressive, often depicting sexual acts and reproductive organs. Like Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas, she is considered one of the YBAs (Young British Artists, also known as BritArtists). Drawing on a recent transformative experience, Emin continues to explore the profound and intimate moments of her life with renewed intensity.

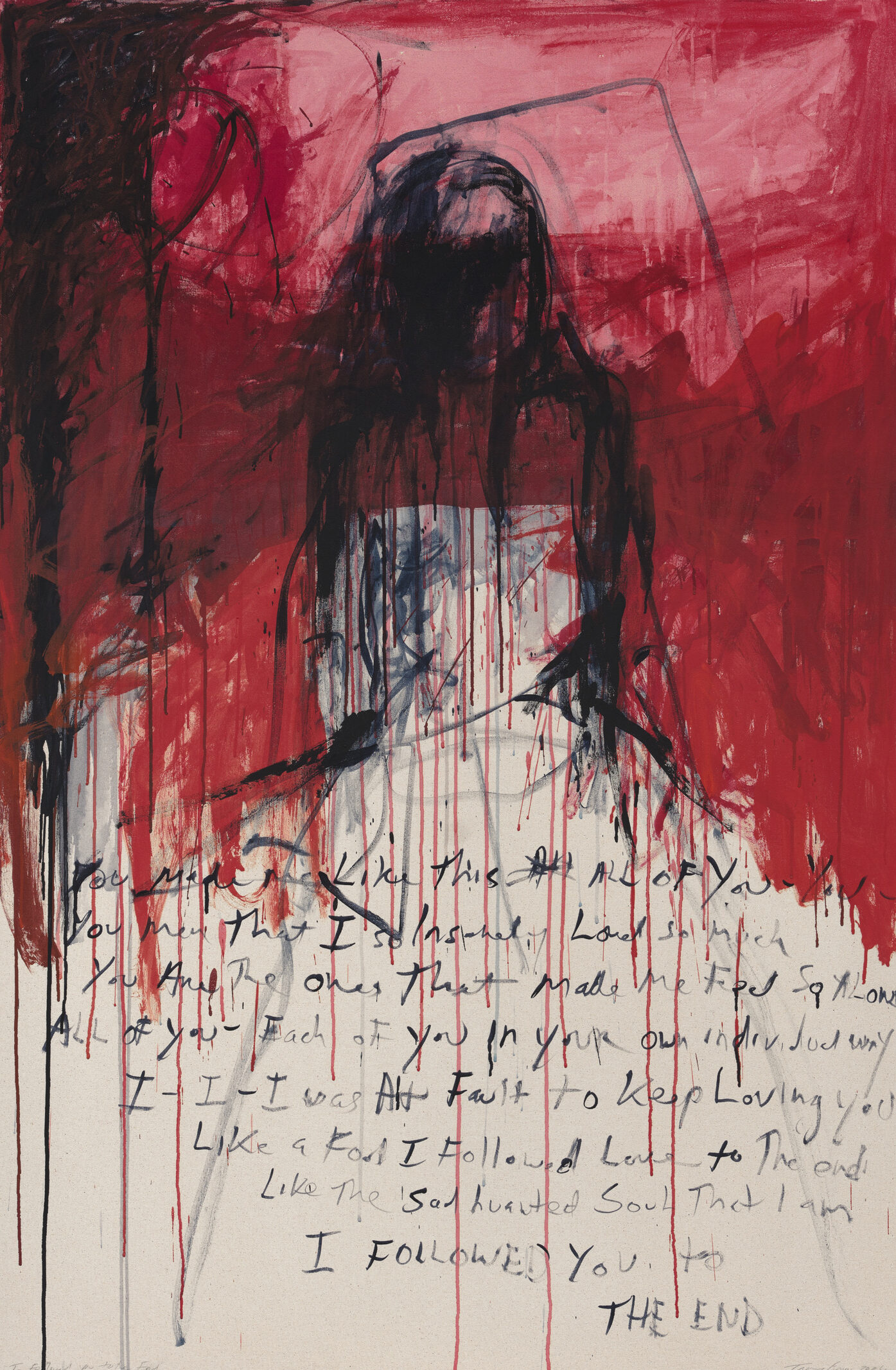

The exhibition celebrates Emin’s expressive painterly vocabulary, focusing on the medium that has occupied and engaged the artist in recent years. Deft, impulsive brushstrokes capture figures in the throes of becoming, while a palette of carmine, ivory, deep blues, and black tempers the volatility of physical and emotional states with intervals of contemplation and stillness. Serving as the fulcrum for the exhibition’s psychic journey, the titular work I Followed you to the end (2024) elicits the plaintive anguish wrought from the complexities of love. Bathed in a tempest of red and black, the silhouette of a solitary female figure is framed by a handwritten exhortation to the lovers who mistreated her:

You made me like this. All of you – you – you men that I so insanely loved so much. You are the ones that made me feel so alone. All of you – each of you in your individual way. I – I – I – was wrong to keep loving you. Like a fool, I followed love to the end. Like the sad haunted soul that I am, I followed you to the end.

From this wounded indictment, tensions emerge in other works, where the mourning of lost love is countered by a visceral drive for self-preservation. In the diptych My Dead Body – A Trace of Life (2024), the female subject lies supine, her pelvis thrust upward while her head sinks beneath a crimson tide. This horizon line extends to the second canvas, where a passage declares: “I don’t want to have sex because my body feels dead.” Informed, in no small measure, by the artist’s recent confrontation with a life-threatening illness, the work also speaks candidly of Emin’s personal reckoning with mortality. The private spaces that Emin’s subjects inhabit – beds and baths – transform into sepulchral vessels, securing the figure within.

Emin approaches her paintings without preliminary sketches or a predetermined vision, interacting with the canvas as if it were a medium of divination, bringing hidden truths to light through the painting process.

In many of the works, the veil between life and death is thin and permeable, a diaphanous threshold through which the artist’s figures seem to make contact with the Beyond. Similarly, Emin’s instinctive process involves veiling and unveiling: she often paints an image on the canvas only to obscure it later with additional layers of white, leaving behind a spectral impression of the overwritten form, as can be seen in Take me to Heaven (2024). Here, the subject assumes a tranquil repose, as if floating into another realm. To the left, a pale lavender presence – evoked through this technique – appears beside the protagonist, serving as a surrogate for the artist’s deceased mother. Depicted within a room adorned with blue floral-patterned wallpaper, the serenity of the scene is suddenly ruptured by a violent gush of red pouring from the subject’s torso, wrenching the transcendent moment back to the immediacy of the present.

Similar decorative motifs appear in works such as The End of Love, More Dreaming, and Our World (all from 2024), which draw inspiration from the intricate designs of Turkish rugs collected by the artist, who is of Turkish descent herself. These patterns represent a different form of mark-making, one guided by a meditative impulse rather than the frenetic and urgent fervor that often characterizes her paintings. Inspired by the evocative domestic scenes of Edvard Munch, the settings within these compositions become as integral to the narrative as the figures themselves. Autobiographical markers are woven throughout the work, as in The Bridge (2024), where an undulating landscape – suggested by the silhouette of a sofa – symbolically connects the artist’s two hometowns, Margate and London, with the sofa’s posts evoking the structural supports of the Medway Bridge. Throughout the exhibition, the artist’s faithful companions – her cats – reappear across both large canvases and small-scale paintings, either gathered around the solitary figure or standing as stoic sentinels, silently keeping watch. In The End of Love, they serve as surrogate subjects, filling the void left by the stained silhouette of the two lovers, now erased and absent from the bed.

For further information whitecube.com.