JENNIFER GUIDI IN CONVERSATION WITH NICOLA GRAVINA.

NG A great abstract painter once said that people accept pure emotion from music, but from art they demand explanation.

JG It’s true. I wonder what’s the reason. [laughs]

NG I think it’s an issue affecting the relationship between personal and collective dimensions. Two realms that, in your work, have intertwined in an interesting way. Regarding your gradual transition to abstraction, you have told me how the audience became deeply interested in your work once you related to it in an individual way. In other words, your work reached a high relational level when started focusing on your personal.

JG Yes, during my transition to abstraction, I wasn’t represented by a gallery and didn’t exhibit for many years. I think having that time to be on my own in the studio, not allowing anyone in or having anyone’s opinion, gave me the occasion to contemplate, which was very freeing. An artist friend of mine would not let anyone into his studio before his work was finished, and he told me: “Don’t let anyone kill it before it has time to grow and live.” I liked that. It has been a long transition. Abstraction was a new territory, and I had wanted to make that move years before, but I didn’t feel ready yet. Coming from a representational background at Boston University, where I learned to draw and paint from the figure and from still life, I feel like I was recording a part of my life in terms of painting myself, my friends, or interiors that I lived in. My figurative paintings started becoming flatter and more about pattern, I was trying to shake out all of the images. I became very interested in the backgrounds I was painting, that were of a solid color. I love Agnes Martin’s early monochromatic paintings, but I have never considered myself a minimalistic painter. The real turning point was when I decided to make something that was more about mark-making and the repetition became a meditative process of its own. In this way I was able to make a body of work that became a quiet example of my personal journey. When I had a number of paintings completed, I felt confident that I was making something that was truly my own. At that time I finally allowed people back into the studio, and it was very exciting because they understood what I was trying to convey.

NG Could you discuss about how you created these early abstract paintings, the techniques you used, and the main inspirations that led to the transition?

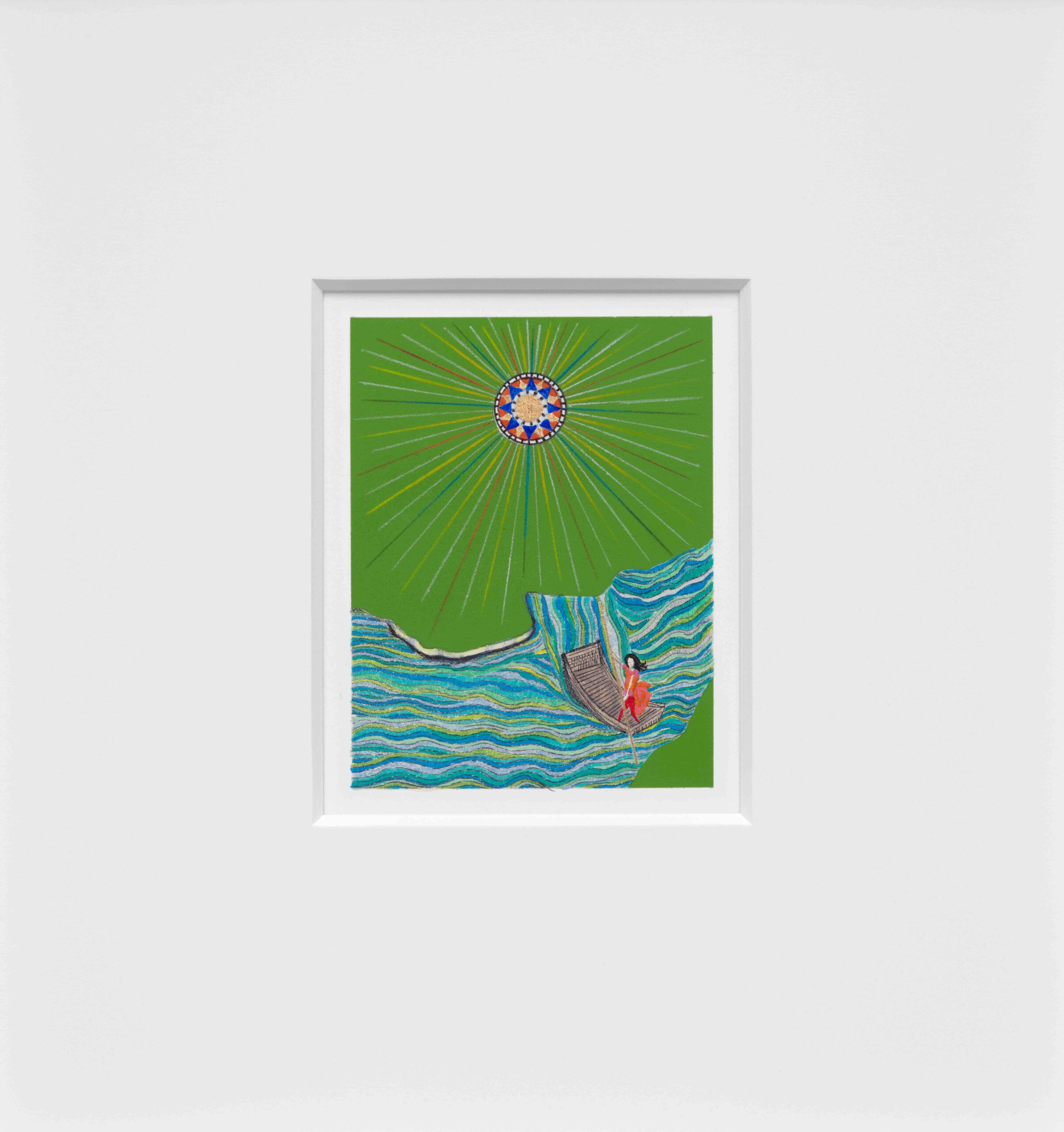

JG In 2012 I traveled to Morocco and I brought back several rugs. My move into abstraction started when I began taking photographs of the stiches and random patterns on the back of the rugs. I made a series of small paintings on paper from those pics, which lead to a larger body of work on canvas.

NG You told me how you felt restrained from figurative painting. Yet, sometimes figures re-emerge in your even recent drawings.

JG In terms of those drawings, when figures started to re-emerge, I was thinking of them more as metaphors that leant themselves to the overall story that I was trying to tell. These mystical images are also sometimes hidden in my paintings by the top layers of sand and paint, but even when they are not visible, their energy still affects the perception. These symbols are part of a broader personal and collective story.

NG Talking about your meditation practice, you explained how the ideas come to you, beyond any possible plan. In a way, this reminds me of the Byzantine icon painters, who executed a core group of basic motifs, in the belief of being instruments of a supernatural light-image pouring into the artwork through their hands. In this respect you mentioned the notion of inspiration, not in the sense of Romanticism, but more as reference to the sphere of meditation, in relation to Eastern cultures. I am very interested in your attitude to converge different cultural elements on the canvas, from Goethe’s color theory to Tibetan mandalas.

JG In my meditation practice, which I have been doing for many years, there’s an openness that happens when sitting still. I think meditation helps me get there, because it fosters awareness: if you’re sitting still and you’re open to thoughts and ideas, they’re just going to come to you. Of course there are other ways to find inspiration and experiencing enlightening moments that lead us to find solutions. I think we all live those moments where you’re in the zone and you know you’re in a different state of mind. Agnes Martin said she would just sit and wait for a vision. If you are a visual person, eventually an image, a color, or an idea will surface. A lot of times I will try to work out it my mind how to make something new and there will be that moment when I suddenly know how to accomplish it.

NG Agnes Martin also said that she painted “with her back to the world”. I would say you have a greater propensity to openness.

JG Yes, it is different. She was an artist who preferred to live in solitude and work without any outside interference. I definitely like to be connected to people. We were talking about using colors to connect to people, how it evokes emotions and joy, and that really interests me. Recently I had a show at the Long Museum in Shanghai; unfortunately, I wasn’t able to go there due to travel restrictions, but I received so many messages from people who had just come out of a serious lockdown, and they were so happy to go out to see art.

NG In your art this kind of connection and communication also occurs through the evocation, for example in titles, of scientific concepts such as energy and magnetic fields. This possibility of moving people through force fields seems crucial, also in relation to compositions where signs originate from a central focal point and expand toward the viewer. Should it be interpreted as a metaphor or something more?

JG I think it is real! Standing in front of the painting, I myself am surprised. It’s like when you create something and you’re in that altered state, in that zone, then you feel a sense of detachment, almost wondering if it was you who created the artwork. Suddenly the artwork is there, it exists, and standing in front of it you feel this energy and movement. I feel that the energy we put into something also comes out of it.

NG Yes, a kind of physical and deep communication. Beyond this relational dimension, is there something else in your practice that you think is fundamental, but is hardly conveyed to the viewer?

JG For me creating an environment is important; I designed, for example, a circular room to accommodate twenty-two of my drawings in a solo booth with David Kordansky for FIAC Paris October 2019. I was apprehensive about showing my small, framed drawings at a fair. I wanted people to slow down and take their time to contemplate the work. Then I began to think of a room. A special place to be carried out of the fair and into someplace quiet, more domestic. I began to design this room in a maquette and then taped out the plan in the studio. Within this circle it just worked out that it fit twenty-two panels perfectly, leaving one space free as a doorway. I covered each panel with black sand and found a black carpet for the floor. It created an intimate environment in which to view the work. In my new exhibition there’s a rock garden, and I designed all of the elements of the installation, down to the type of gravel used. A lot of times I find that people don’t realize that is also part of my practice. When I curate a show, I take a more holistic approach. I work with a maquette in order to create a more immersive experience. I consider the architecture, I decide which paintings will hang next to each other, how they play with each other, and how the color bounces from one to another, that’s also very important to me.

NG This made me think about how you have been influenced by artists using architecture to create domestic environments. You told me about your love for Robert Gober’s rooms, and how you had been impressed by Louise Bourgeois’ Cells; about how in your living space you feel like you are constantly curating, and even as a child you needed to see how things worked in space. It seems that this attitude informs not only your practice, but also the other aspects of your life.

JG I feel it goes into every aspect of my life, it is not just on the canvas. The studio itself is an expression of me. In a way, I want to control the environment I am surrounded by, including my home, how to arrange it, and curate it, and also just building. I think of myself as an artist, I’m making things, but I’m also like a builder in a certain sense as well. All humans are. I can constantly look at cities, you know, everything we made from ancient time to now, it’s amazing, we’re constantly trying to build, and create and improve. [laughs]

NG Yes, the issue of control over the exhibition environment is fascinating. We tend to draw attention to the role of visitors in constructing a personal, interpretative path, supposedly free from curatorial prescriptions. But often the absence of guidance results more in the oblivion of the audience than in its freedom. It is also through these dynamics that visitors become part of a whole, completing, if you will, the exhibition. Is there anything crucial you learned from the audience that you didn’t expect?

JG In terms of social media, when I first joined Instagram, I wasn’t posting art, I was just taking photographs around Los Angeles and they were mostly of architecture, studies of shape and color, and how the light hits the wall. For me the energy that I got back from people, positive feedback at that time, was really important. I felt very hidden, I’d had a couple of shows, but nothing happened with them; at that point, in the early 2000s before social media, if a gallery, or a museum, or a curator wasn’t pushing an artist, there was no way for people to really know about you. So, I saw social media as such an amazing platform where people were being very supportive, and it was really a way to be seen, realizing that people are interested in seeing through my eyes, in how my brain works visually. Then when I started showing again, and I had my first exhibition in New York, I had already been posting my work on Instagram. I understood that people got what I was doing, they were responding to it in a very positive way; so, it was another way to kind of gauge that I was on the right path, in terms of connection.

Read the full interview on Muse February Issue 61.