The Osservatorio Fondazione Prada’s spaces are hosting an exhibition exploring storyboards and other materials useful in designing and making a film. There are moodboards, drawings, sketches, scrapbooks, notebooks, annotated scripts, and photographs. It is a survey of film history, collecting elements created from the late 1920s to the present. A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings for Cinema is curated by Melissa Harris, who tells how each filmmaker’s approach may be different, but also how creating storyboards is always part of the process. She recounts how it was not easy to source all the storyboard material for the occasion, how important it was to draw a common thread that also had consistency within the spaces. Drawing for some is a design element, for others it has a visual function, and for others it serves the correction of storytelling problems.

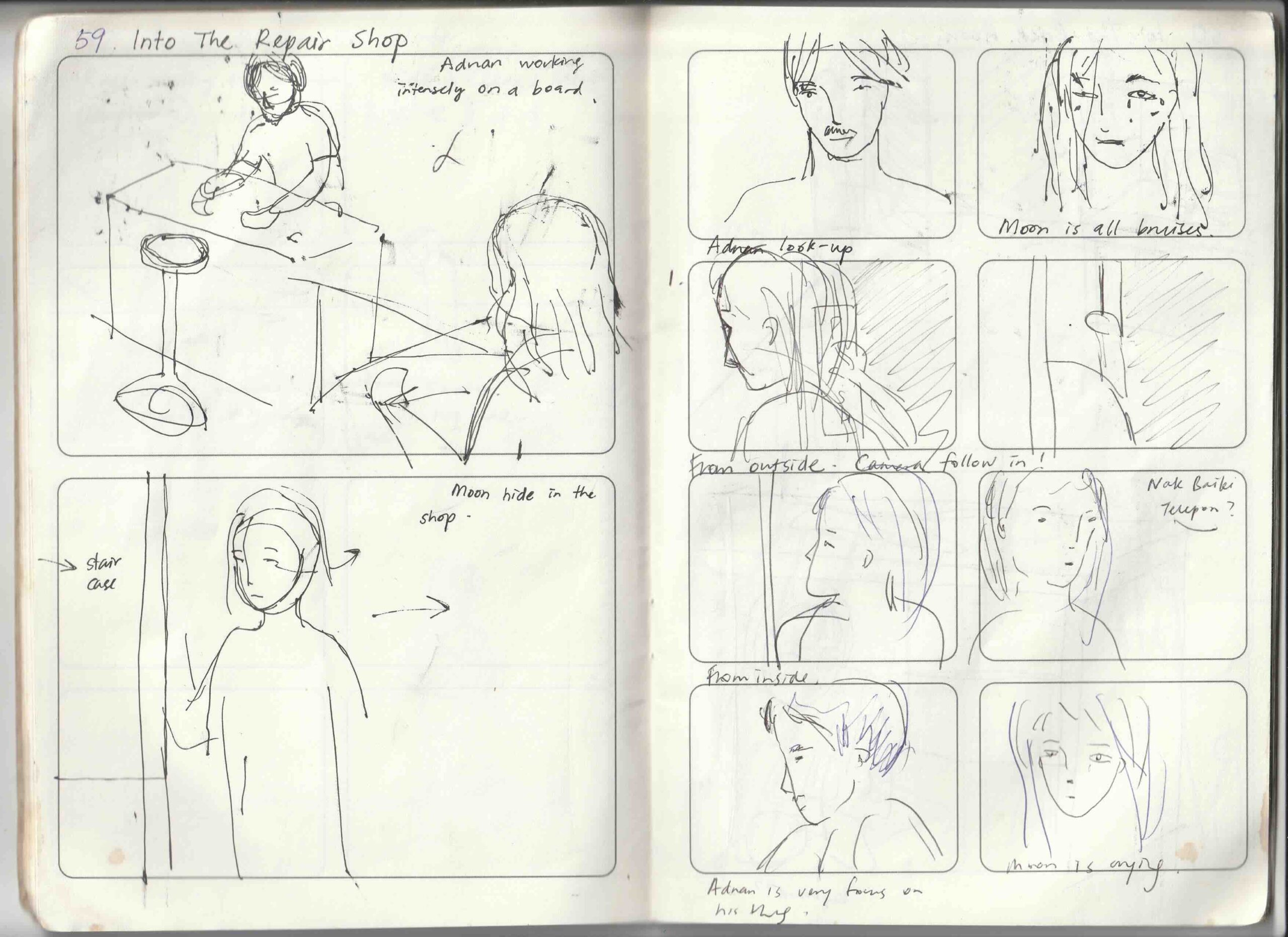

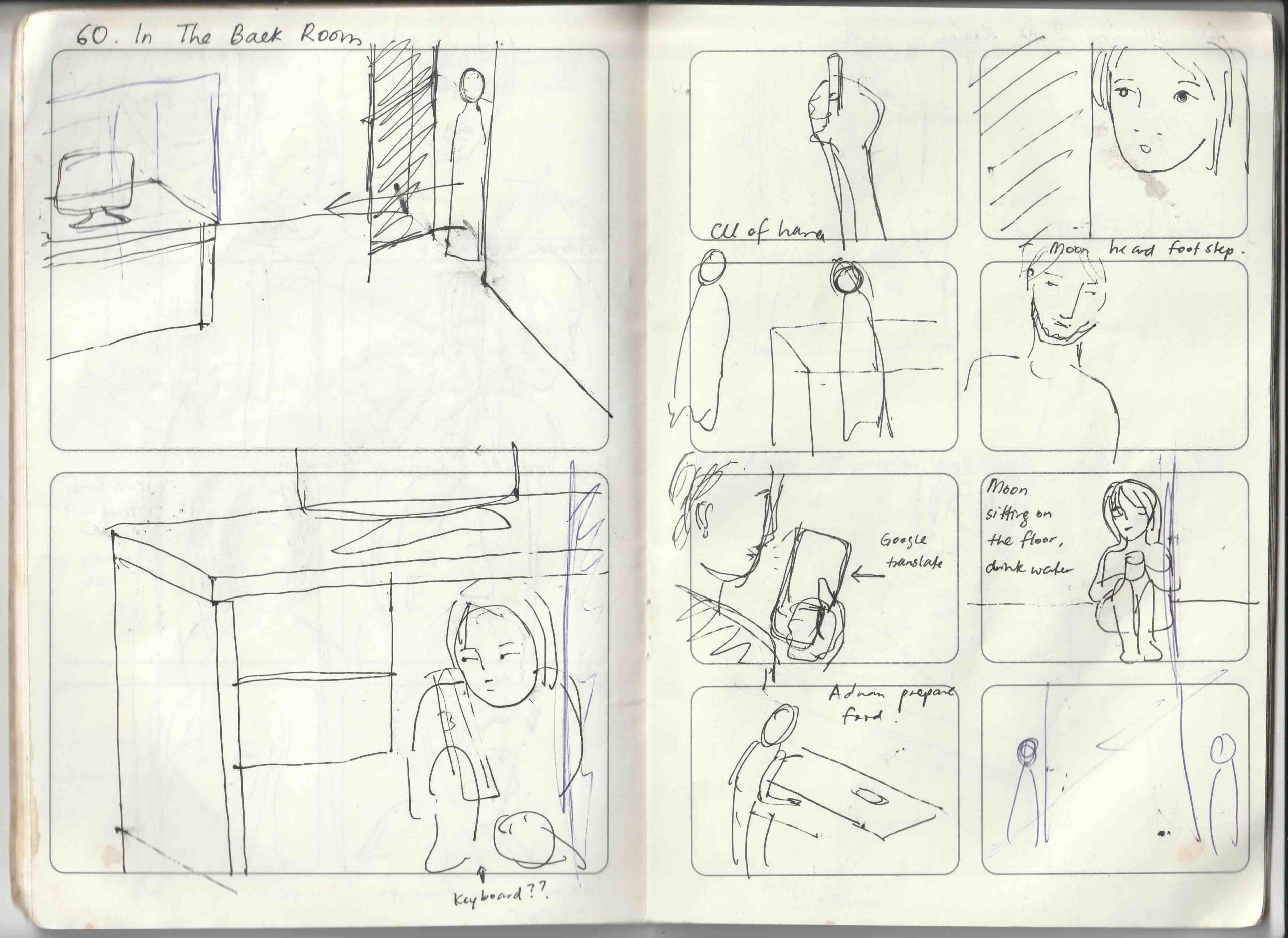

Storyboards actually serve a dual purpose, first to represent the director’s creative vision and later to become a tool for the technical realisation of scenes in a film. They are essential, therefore, to reflect, dose, understand, and actually enter the story. They play a key role. They represent the primordial visualization of ideas that are then materially realized. The process, the collaboration, the human character, the ideas, are all part of the starting point of a much deeper and more complex process.

The layout is designed by Andrea Faraguna, of Sub architectural firm. The very arrangement of the pieces takes inspiration from the structure of a storyboard, the starting point and essential tool to the composition and communication of the process that leads to a finished product.. The environment evokes the artists’ work in an immersive, spatial experience. Each table on display is dedicated to a specific film and features its counterpart suspended from the ceiling, creating a funnel effect toward the unique perspective on the city. This visual puts Osservatorio Fondazione Prada’s interior spaces in dialogue with the special and powerful architecture of the space, a window to Milan’s rooftops and the vaults of the Galleria. The arrangement of the exhibits is like a succession of scenes within a film. The rhythm that has been recreated is fluid, flowing and pressing, guiding visitors as if they were passing through several frames of the same film. The goals of these useful tools in filmmaking are different: defining the sense of place, the identity of one’s characters. In studying these approaches, substantial methodological differences emerge between European cinema and the American approach; if the former involves a more artistic and artisanal line, the latter winks at productivity and efficiency. All the elements that directors, writers, and screenwriters use to write scripts have the quality of being considered true works of art, unique and personal, pointing to facets that remain hidden behind visual aspects that seem seem to us to be entirely clear. Every aspect of any realization has a far more intimate depth than what we imagine in observing the finished scene.

Osservatorio is Fondazione Prada’s place dedicated precisely to the research of visual languages. The exhibition is a paradigmatic journey through an atmosphere dedicated to experimentation. Underlying the research for the exhibitions is the study of possible commonalities between technology and various cultural expressions. This time it is the storyboard that is the precursor to animation projects of any kind, representing the trait d’union between the person and the narrative, between the director and the scene. It serves the team, as well as the image, to understand exactly what is good to make and what is not, what is the point of view to respect and what needs to be revised and modified. The origins of the storyboard, though ancient, are still visible and rooted today, in its usefulness, in its being a tool for improvement, in its specific characteristics. The central element of the entire installation is the drawing board, the slanted plane that calls to mind the focused perspective of traditional creative processes related to cinema, but also the direct view of a point of view, of the author’s own work space. The space is that of creative work, the place where ideas are created, where scenes are framed, where the precise hand that fine-tunes the initial idea allows itself to be read and discovered.