Harley Weir, The Garden

Hannah Barry Gallery, London

From June 5th until September 13th, 2025.

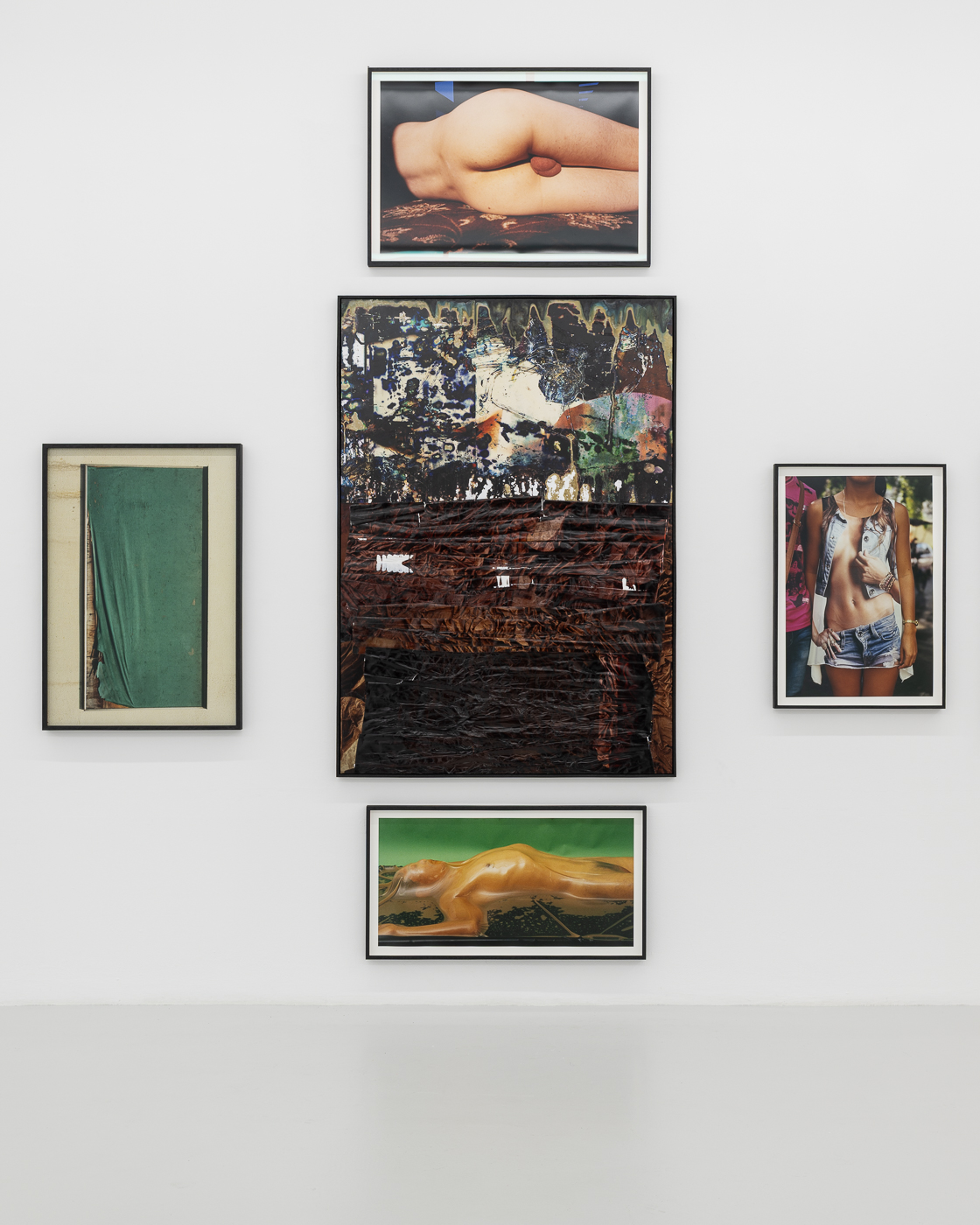

In The Garden, Harley Weir transforms Hannah Barry Gallery into a mythic compost heap-where memory decays, the body moults, and desire ferments. The title, deceptively pastoral, conceals a deeper, darker soil: not Eden, but aftermath. Here, the garden is less a place of innocence than of intimate ruin, where relics of girlhood and womanhood collapse into one another, forming a psychic terrain that’s more archaeological than idyllic.

Weir’s work has long occupied the space between seduction and exposure. She builds images the way one might build a shrine, obsessive, luminous, and slightly off-kilter. In The Garden, this sensibility finds a new register. The show is divided across two floors, though it might be more accurate to say it is split across two psychic terrains. Downstairs, adulthood is rendered as both theatre and reckoning. Through photographs that oscillate between tenderness and unease, Weir maps the dissonance of care-motherhood as both cradle and constraint, the body as both vessel and clock. These are not answers, but ruminations. Weir is not documenting a stage of life so much as tuning into its frequencies-the hormonal feedback loops, the unphotographable ache of shifting roles.

Upstairs, the register shifts from elegy to reverie. Weir presents 28 new works—hybrid artefacts made from handmade paper, photographs, dried flowers, butterfly wings, and archival letters sent in the pre-digital ‘90s and early 2000s. These pieces feel like devotional objects from a teenage reliquary: part botanical index, part adolescent confession. They resist nostalgia in favour of something more unruly—a kind of temporal entanglement where innocence and obsession blur. There’s an intelligence in this disorder, a refusal to cleanly separate past from present, pleasure from grief.

At the heart of the exhibition lies Sickos, an ongoing series born in the darkroom and steeped in alchemical experimentation. Here, the photograph is no longer a still; it’s a body reacting, dissolving, bleeding. Weir introduces blood, sperm, contraceptive pills, perfumes, and hormones into traditional chemical processes, turning development into an act of transformation.

Weir’s ability to wield both precision and chaos is perhaps her most radical gesture. Her work sits in opposition to photography’s traditional machineries of control – the frame, the capture, the decisive moment. Instead, she conjures images that leak. They are porous, unstable, feral. In this sense, Weir belongs less to a lineage of documentarians and more to that of the witches, the mystics, the chemists of feeling. Her photographs do not freeze time, they ferment it.

“The pinnacle and the pipe dream of where I’m going.”

Skin, memory, desire-even care itself-appear in Weir’s work as precarious substances, prone to bruising, soft to the touch. Her images behave more like weather systems – fleeting, atmospheric. One is drawn into them as into a cloud of scent or a half-remembered feeling. If The Garden gestures toward paradise, it does so only to reveal the artifice of the idea. There is no neat vision of Eden here-only compost and contradiction: mud, flesh, archive, and longing. And yet from this fertile disorder, something luminous emerges. Not quite hope, but a form of exquisite decay. Rot that nourishes.

Weir calls the garden “The pinnacle and the pipe dream of where I’m going.” One imagines she’ll never get there fully. The beauty lies in the attempt, the dig, the mess.

For further information hannahbarry.com.