Try to imagine the procession that accompanied Cleopatra when she arrived in Rome exactly 2,073 years ago. It must have been such a lavish and bizarre spectacle that any attempt at imitation would pale in comparison: naked dancers, ostrich feather fans, drums, enchanters with arms wrapped in dozens of snakes, and handmaidens scattering ambergris from large colorful jars. Amid the parade stood out a group of strange priests, their bodies shaved up to their eyebrows, dressed in long linen tunics tied at the waist and embroidered with lotus flowers. Watching them chant as they moved along the triumphal way must have been quite a sight.

And yet, few Romans were truly impressed by this strange apparition. By then, Rome had long grown accustomed to living alongside the followers of Isis. The cult of the Egyptian goddess—who promised fertility and resurrection—had reached Italy decades earlier, whispered from mouth to mouth along the docks of Alexandria, carried in the holds of ships, and finally spread into the salons of Roman matrons, who, along with the name Isis, were learning to pronounce others, ever more exotic. Rome was already becoming a kaleidoscope of diverse cults. After all, tolerance—including that of religious practices—was a vocation rooted in the city’s founding values. Romulus himself had established an asylum on the Capitoline Hill—a refuge meant to welcome foreigners, exiles, runaway slaves, and anyone who wished to start a new life. It wasn’t just a physical space, but also a political act: it enshrined the right to asylum as a cornerstone of the new Roman society. The idea was that anyone could become a Roman citizen—not by birth, but by choice. And although the more conservative fringes of the Senate had always opposed—and at times even banned—the most nonconformist religious practices (as the early Christians well knew), contamination was inevitable and astonishingly fertile.

When Rome later became an empire, things grew even more complex. Under the dome of the Pantheon, a temple consecrated to all the gods, worshippers from three continents now gathered. Its massive cupola, with its oculus open to the heavens, already seemed to suggest to the crowd below a more cosmic and universal belief—one that transcended the various representations of the divine. Just steps away, Isis had by then her own temple, dense with obelisks and sphinxes, at the center of which stood a bronze ablution fountain shaped like a pine cone—the very same that today decorates the famous courtyard in the Vatican. Meanwhile, far from the colorful and multiethnic crowds of the Campus Martius, in their suburban villas, the young scions of Rome’s most prominent families gathered in underground basilicas to celebrate the teachings of Pythagoras, surrounded by delicate stucco figures dancing in the dim light of oil lamps. One of these rooms still exists today, hidden beneath the train tracks just outside Termini Station. Entering it now, the vibrations of trains passing fourteen meters above seem almost like the echo of a hushed prayer. But let us return to the ancient world. By the time the Empire was waning, religious fervor had penetrated every layer of society—from the rooms of the palace on the Palatine Hill, where the young emperor Elagabalus married two men and two women at once according to the rites of his god, to the underground galleries of the Baths of Caracalla. There, amid the fumes from the furnaces and the roar of carts full of firewood, one could hear the hypnotic voices of Mithras’ followers chanting ancient Persian melodies.

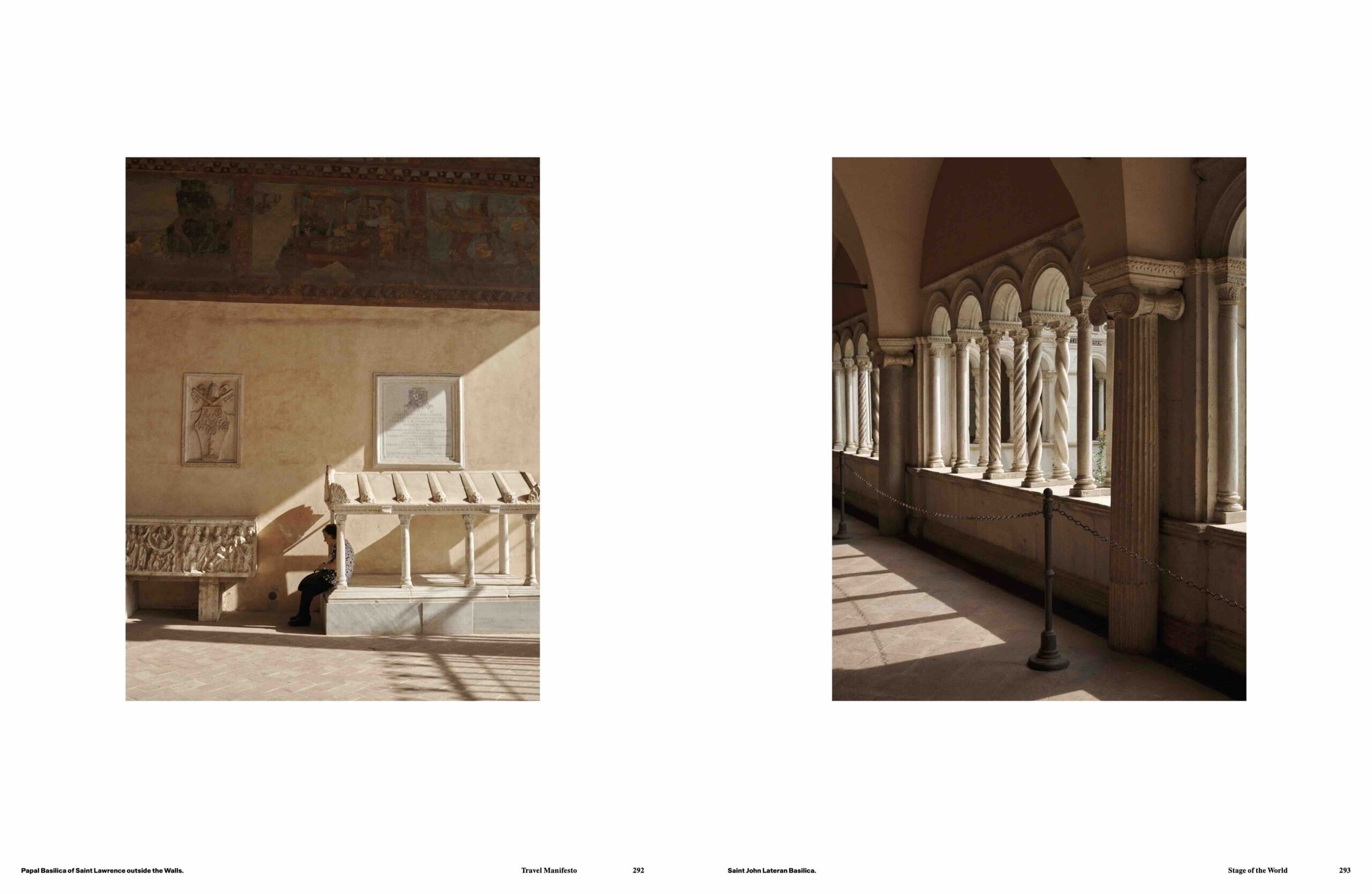

And if still in the 5th century, at the full collapse of the old gods, a young pagan named Symmachus could declare before the Senate that “everyone is free to seek the truth in their own way,” it means a flicker of ancient tolerance still managed to survive. At first glance, these were the last sparks: for over a millennium, the monolithic Christian religion would suffocate every heretical impulse. Yet beneath the sometimes suffocating layer of Catholic orthodoxy, the city continued to simmer with syncretism. In the early Middle Ages, for instance, the arrival of Eastern popes turned Rome into a Byzantine stronghold, and in the city’s crumbling streets one could hear Greek, Syriac, and even various Anatolian dialects.

In his Journal de voyage en Italie, Montaigne recounts a curious fact: in the church of San Giovanni a Porta Latina, some men had staged same-sex marriages. Still visible today is the so-called Alchemical Door, a curious artifact hidden among the gardens of Piazza VittorioEmanuele, telling tales of alchemists, secret formulas, inquisitions, and elixirs of eternal life. But if you look carefully, Rome is dotted with places linked to alchemy—like that of Cardinal Del Monte: a tiny jewel box tucked inside a Casino di delizie, its ceiling painted by Caravaggio. Or the mysterious Etruscan Room commissioned by Prince Torlonia beneath his villa on the Via Nomentana, decorated like an ancient tomb to host Masonic rituals. These are clear imprints of a never-quenched vocation. And speaking of imprints—try looking at the Municipal Rose Garden on the Aventine Hill from above. You’ll instantly notice the shape of a Jewish menorah, a tribute to the ancient cemetery that once stood there. And what about today? Today, Rome appears as a confused metropolis, its skyline still dominated by the dome of St. Peter’s. Yet the truth is that Rome continues to radiate extraordinary spiritual vitality, which struggles to emerge amid bureaucratic obstacles and ideological battles. The Rome of the new millennium pursues its universal vocation with the mosque designed by Paolo Portoghesi—the largest in Europe. In recent years, at least six Buddhist temples, several Hindu centers, and even a Taoist temple have opened. Rome remains, to this day, the city with the greatest diversity of faiths in Italy. A phenomenon that might offer a glimpse into its future vocation.

Discover the full Travel story in Muse Issue 66.